Every year, Nicole Watkins’ grandmother brings a special sweet potato casserole dish and a cranberry mix to Thanksgiving dinner in her Irvine, California home. Sitting around the table to eat with the Dallas Cowboys game on in the background is an important tradition for the first-year creative writing major. But this November, Watkins will be celebrating it from behind a screen door or on another side of the house.

Her 85-year-old grandmother faced a recurrence of breast cancer during the pandemic. The combination of her age and chemotherapy treatments put her at an exponentially greater risk of contracting a severe or deadly case of COVID-19.

“There’s so much exposure that comes from traveling,” Watkins, who considered not coming to the Boston campus after her grandmother’s cancer resurfaced, said. “It’ll definitely be different, so I’m sad about that, especially because traditions are so important, especially in my family.”

With less than a month until students are slated to vacate campus until the beginning of the spring semester, Watkins and other community members with immunocompromised loved ones are staring down one of the consequences of returning to in-person classes. COVID-19 cases across the country are climbing, and travel, especially in urban areas, poses a massive risk. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that traveling increases a person’s chance of contracting and spreading COVID-19, as it involves high-volume and high-contact areas like airport terminals and bus depots.

First-year student Cameron Arendt, whose 21-year-old brother, Ryan, was diagnosed with bone cancer in May, said he, too, is fearful of the idea of flying home to northern Virginia.

“I would definitely be more comfortable if [my parents] drove up, and then picked me up, and then drove back down even though that’d be a long thing, and I don’t expect that to happen,” he said. “I think flying makes me nervous about it.”

Following a strict quarantine with his family over the summer to ensure Ryan’s safety, Arendt said he was able to ease some of his restrictions once he came to the Boston campus.

“It was definitely refreshing to meet new people and kind of live a normal life,” he said. “[When I go home in November] I’ll definitely go out more than I did over quarantine before coming here, but [I’ll be] still very cautious about it.”

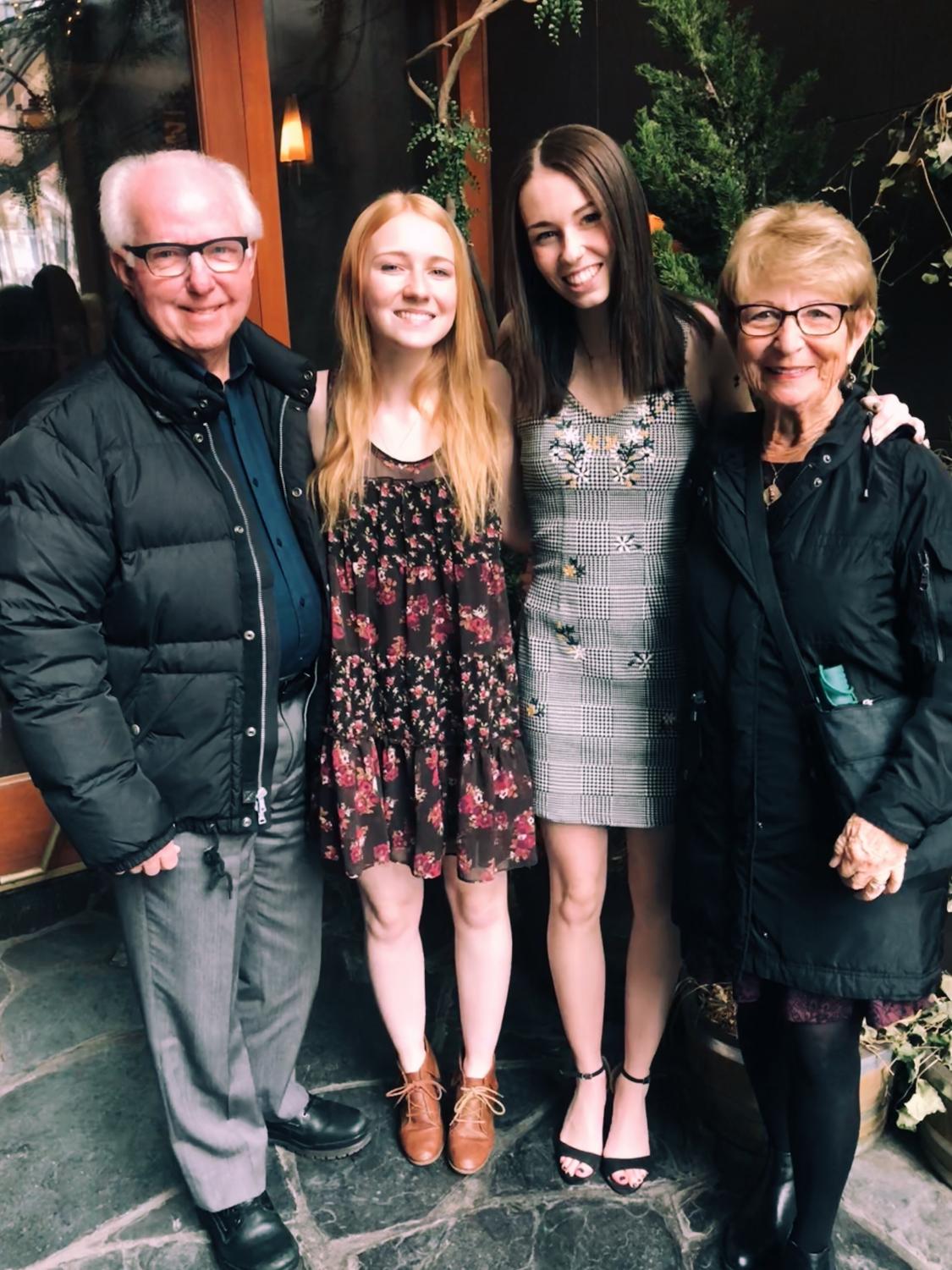

For some community members, seeing older or immunocompromised family members has been made virtually impossible by in-person classes. Writing, Literature and Publishing professor George Baroud hasn’t seen his grandmother, who is in her eighties, or his mother, who is 64, since the semester began. He’s fearful that, at their age, the consequences if were they to catch the virus would be dire.

“My biggest concern is it’s hard to be supportive of family when you can’t see them,” Baroud said. “[My grandmother] thinks I don’t want to see her, but it’s really like, ‘No, I have to try to protect you.’”

While Baroud said he hoped he would be able to spend time with his loved ones after in-person classes concluded, the weather will complicate these plans.

“Over the summer, whenever I was with my family, it was always a controlled environment,” he said. “I would insist that we meet outside, masks on, six feet [apart], and that’s not going to be very easy to do in December.”

Baroud initially advocated for a fully online fall semester, an alternative administrators said could cost the college up to $100 million.

“I was very much in favor of going completely online because I thought, for a whole variety of reasons, it was more equitable for everyone and the safest option,” he said. “Once it was clear that the administration wasn’t going to go online, I decided to support the administration because that was just the reality on the ground, and that’s why I’m teaching in person.”

For community members who are themselves vulnerable to COVID-19, the risk of travel or in-person learning is all the more heightened.

Brooke Knisley, a professor who is disabled and immunocompromised, received accommodations to teach all online this semester. Knisley, whose support system lives in San Diego, California, said she would likely die if she were to contract COVID-19, so she anticipates not seeing her loved ones for the foreseeable future. Even if they were to visit her in Boston, she said, the logistics of staying physically separate would be too difficult, as she does not currently leave her house.

“It’s more difficult, just knowing that I can’t do the back and forth,” she said. “It’s not feasible.”

Knisley said she believed that the college opted for a hybrid model for purely financial reasons and was not a decision made with accessibility in mind.

“I really think that, had they been looking out for the best interest, that they would from the get-go planned for fully remote,” she said. “There is some sort of violence in inconsideration.”

To ensure their family members’ safety, some community members are finding workarounds.

Calvin Kertzman, a first-year student from New York City, said he was living under “constant fear” while quarantined with his mother, who is immunocompromised from cancer and Lyme disease. Kertzman’s family is in the process of moving to Long Island, so the plan is for Kertzman and his brother to get tested immediately and then stay in one house while his mother stays in the other until the results come back.

“She kept apologizing for the fact that she is immunocompromised, which really got on my nerves because it’s not her fault,” he said. “If it was a perfect world, then my mom wouldn’t have to worry as much about corona[virus]. We would still be doing all the precautions we could, but I feel like it’d be a lot easier on our family. But that’s not how it works.”

For international students, concerns of potentially infecting loved ones are exacerbated by the risks associated with long-distance travel and safety guidelines in place in their home countries.

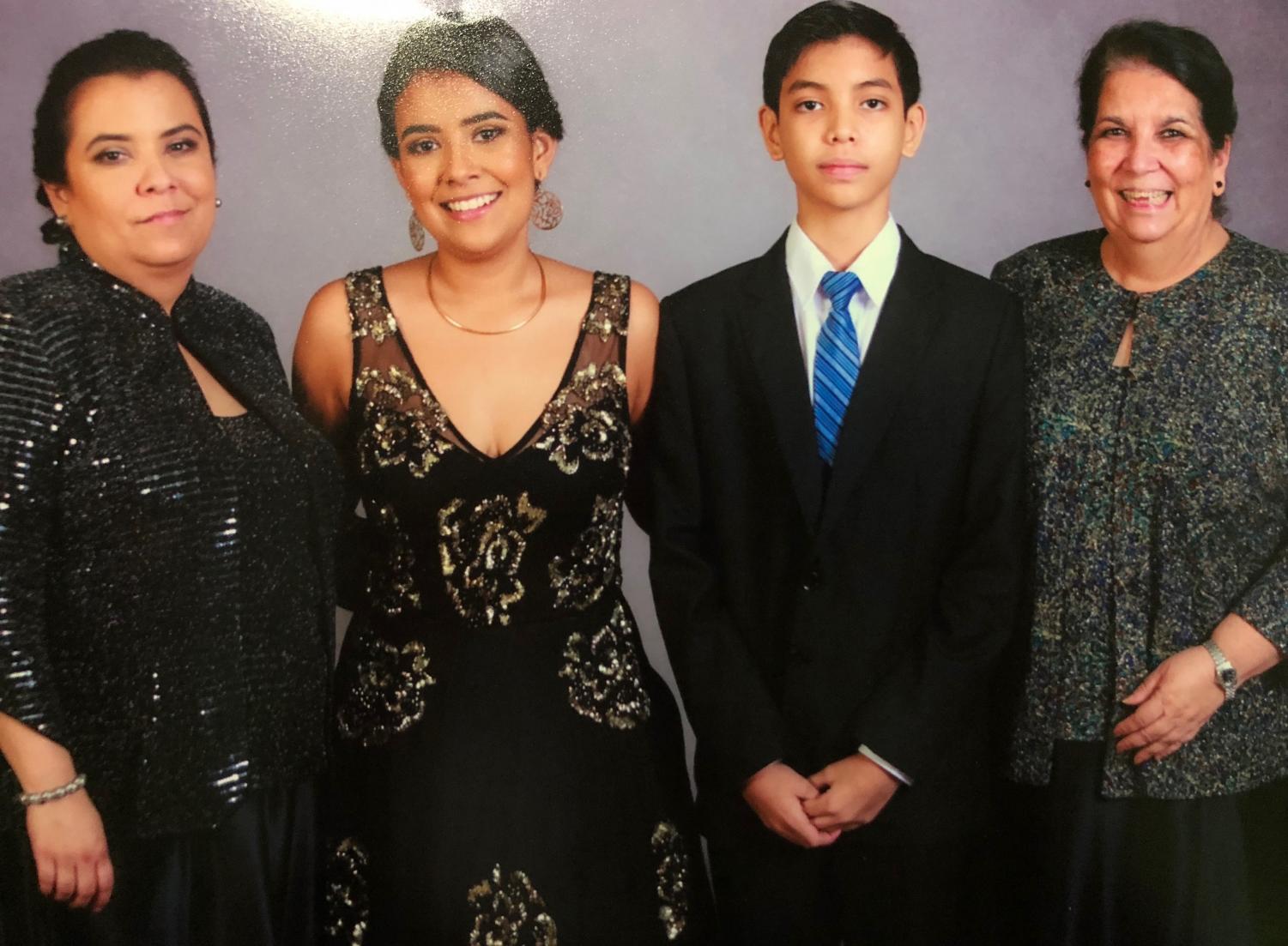

“As an international student, you mentalize yourself that you’re not going to see your family for a while,” junior Daniela Lobo-Rivera, who is from Honduras, said.

Months ago, her stepfather contracted COVID-19 and had to be put on a ventilator. Though he has since recovered, Lobo-Rivera said his continuing health concerns have stoked her fears about returning home.

“I’m absolutely worried that I could give my family members that, and especially my step-dad that went through this has conditions because of this, like, secondary effects,” she said. “I’m going to try my best—obviously get tested, wear masks, and not touch anything in the plane—and basically try my best to be healthy for the sake of my family members.”

Lobo-Rivera plans to fly to Miami, Florida, where cases are currently rising, to meet her mother and grandmother before they all fly back to Honduras. She will have to produce a negative COVID-19 test to enter the country.

Students, despite their concerns, say they don’t see a quick fix that would help them return home with minimal strife. Arendt said it would have helped to give students with immunocompromised family members the ability to leave campus earlier to avoid the rush at airports. Watkins said she couldn’t think of an easy solution.

“If anything, they could have given us time to go home and quarantine before family things, but that also takes two weeks out of the school calendar, so that’s pretty impractical,” she said. “They might have done the best with the situation they were given, but at the same time, it is a little difficult. I just don’t think they were thinking about that when they made plans—they were just sort of thinking about how to get people back.”

Kertzman, who often sees his peers flouting social distancing rules, said he wished the college would stress to students the responsibility they have to keep the community safe, as their actions affect those in more vulnerable populations.

“They’re given a lot more freedom—they just don’t care as much,” he said. “Being on campus is a privilege. I just hate seeing it when people disregard that or take advantage of it and make it worse for other people.”

Lobo-Rivera, who has not seen her family since last December, said the time apart from her family has forced her to grow more independent. Despite the hurdles and stress she’ll have to face, she said she’s excited for the quality time with her family over the holidays.

“I’m going to take every precaution I have to take, and just the fact that I get to be home for a little bit and see my dogs and see my family members,” she said. “I just think that’s the most rewarding part after all this time of not seeing them.”