Cassandra Martinez / Beacon Staff

Last year, I took a novel-into-film class that did not feature a single book written by or about a woman or person of color. The only character of color was unnamed and mentioned in about five sentences in Solaris by Stanislaw Lem. The white women in the other books were all victims and secondary characters to further the plot and development of the white male protagonists, such as: a woman who takes back her boyfriend when he cheats on her, a woman who kills herself when her boyfriend leaves her, and a 12-year-old girl who “seduces” her stepfather.

Although I didn‚Äôt dislike all the books, I felt let down. In the world of these novels, as a Latina woman, I did not exist. In the world of these novels, women exist only in relation to men. With a great, expansive world of uplifting and impactful literature available to us, professors need to present students with more diverse authors and characters. ¬ÝAs the term ‚ÄúAmerican‚Äù continues to grow and expand, it is high time that our canon of literature and the WLP department reflects this.

At the heart of this issue is the existing canon of “great literature,” written primarily by and for white European men. While not always intentional, I’ve noticed a sort of reticence—even laziness—when some academics are asked to break free of these imperialist and classist notions. When several students said the syllabus should to be changed to include more works by or about women and people of color, my professor replied, “It’s just so hard to find good books like that that have good film adaptations,” I wish I had called him out on that lie, and insisted he try harder. I should have told him to do his job.

When I was younger, I would not have questioned this lack of representation. A diverse read was a pleasant surprise, but a syllabus devoid of stories by writers of color was simply to be expected. I was perpetuating a biased, colonialist attitude toward literature because, like many students, I did not know better. Yet, when I was writing in middle and early high school, the main characters in my stories were usually Latina like myself. I did not realize until recently that I needed to explicitly code my characters as Latinx. Otherwise, I fear that Western readers will imagine them as white by default.

The United States loves to call itself a nation of immigrants but often fails to truly promote diversity or allow itself to be represented as more than white. College literature classes are just a microcosm of this same phenomenon. The American literature taught in our classrooms laments the failure of the American Dream, but only through the lens of white authors such as Fitzgerald and Steinbeck, and forget the narratives of thousands of Americans for whom the American Dream was never attainable and never intended for them.

Literature should reflect the real America and depict the stories of different peoples. By doing this, we, as readers and as citizens, can learn to recognize that there is more than one story, ¬Ýand our empathy for fellow humans may then grow. The American experience is more than picket fences and baseball in the yard. America is broad, beautiful, and not just white.

If my professor’s reasoning for the lack of female characters and characters of color in our curriculum was that it was “too hard” to find decent novels by women and people of color with good film adaptations, then perhaps he should have taken an opportunity to educate himself or facilitate a discussion with the class about the problem Hollywood has with financing films not by or about white men.

Now, more than ever, we need to forget the elitist canon of American literature. I am tired of reading white male authors and tired of guys in bars talking about Kerouac and Hemingway in an attempt to impress me. I‚Äôm tired of ‚Äúliterature students‚Äù giving me looks when I say I prefer to read more contemporary literature rather than the canon because I‚Äôm bored of the tortures of white men. ¬Ý

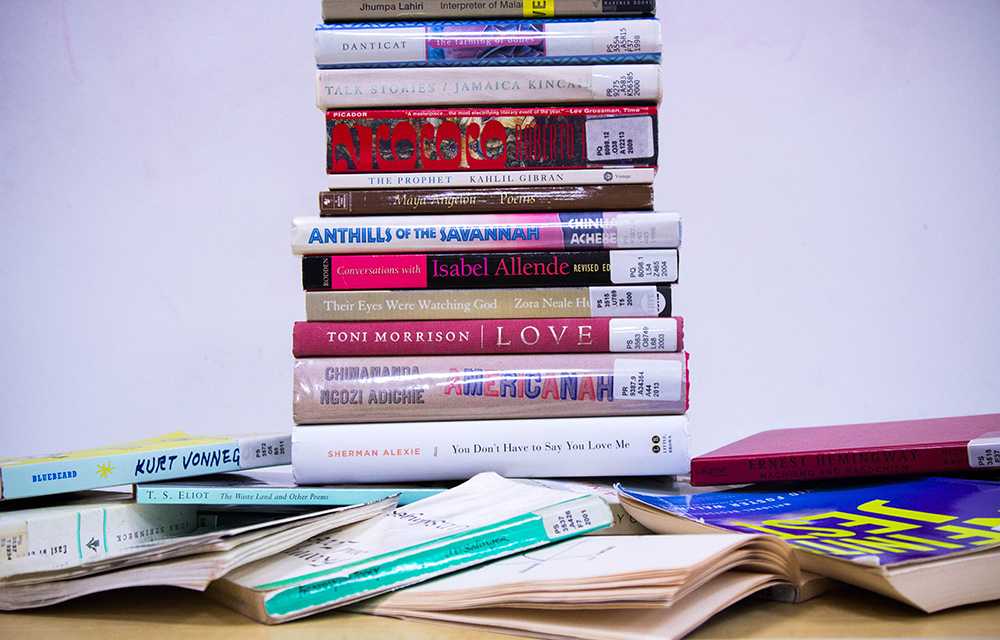

The existing canon of English language literature perpetuates a notion that these are the best writers, that these white men were the only ones producing quality literature worth reading and studying. This is simply untrue. Our classes should be studying Alexie, Anzaldua, and Hurston alongside Fitzgerald, Dickenson, and Poe‚Äînot as the exception or the single diversion from the canon, but as a rule. Emerson provides students with more than an English degree, and the very name of Writing, Literature and Publishing implies innovation and a unique approach. It‚Äôs time that we hold ourselves, and our syllabi, to the high standards of modern literature and to the standards of which our major dreams. ¬Ý