Early Tuesday morning, the Port of Boston was among the many ports along the East and Gulf Coasts that closed as members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) went on strike.

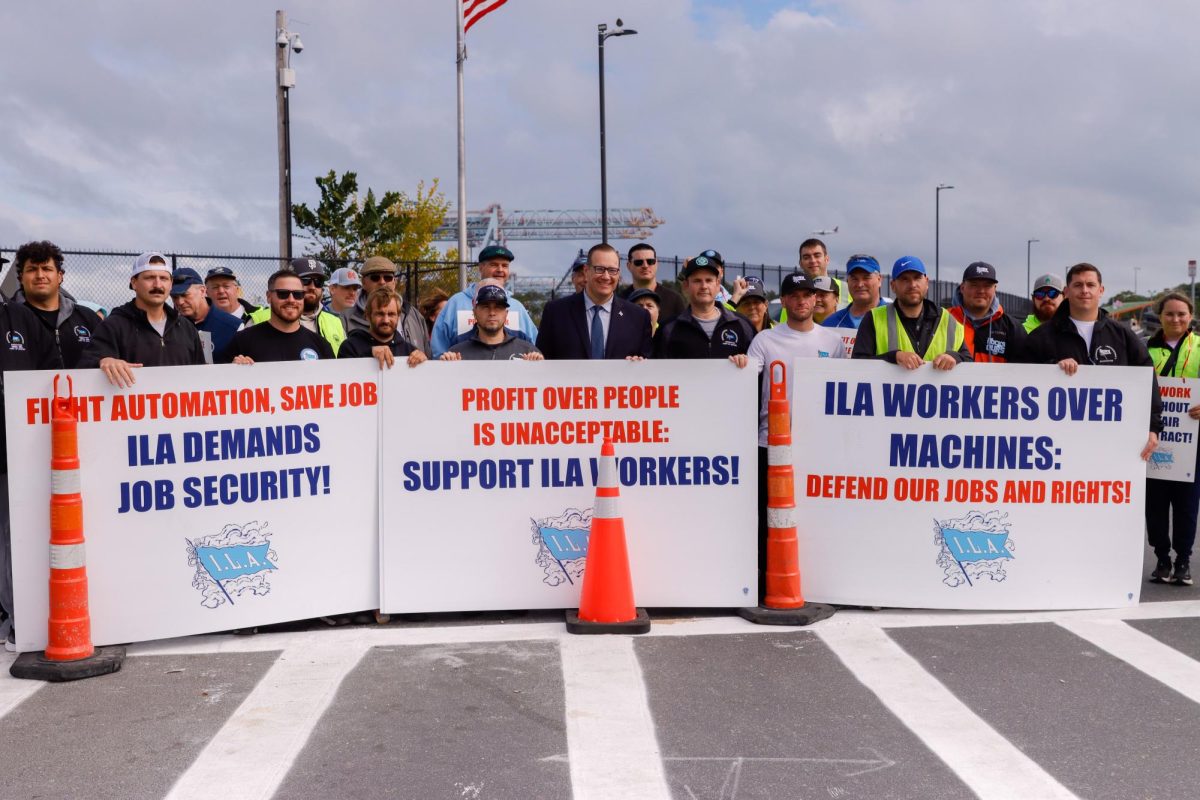

Workers hit the picket line to demand better wages, additional benefits, and make sure their contracts had “absolute airtight language that there will be no automation or semi-automation” said ILA President Harold J. Daggett in a statement posted to the union’s website.

In the statement, it also says “the ILA intends for the demonstrations to continue round the clock, 24/7, for as long as it takes for United States Maritime Alliance (USMX) to meet the demands of ILA rank-and-file members.”

The ILA, representing 45,000 members, went into last-minute negotiations with USMX late into the night on Monday with hopes of sealing a deal before a midnight deadline.

No deal was made, leading to thousands of workers walking off the job just after midnight on Monday.

The USMX represents the port employers.

The ports on the East and Gulf coasts handle about half of all U.S. trade by sea, and a labor strike, if prolonged, could have serious consequences on the economy.

In a show of solidarity, Daggett joined the picket lines in New York and New Jersey and was accompanied by Bobby Olvera, Jr., the president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union which represents port workers in California, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, and British Columbia.

Experts told NBC Boston that the strike could be a $5 billion daily hit to the economy.

However, the total severity of the hit to the economy will depend on the duration of the strike. For now, shoppers won’t notice changes in the stores since most food in the U.S. is domestically produced. Fresh fruits could be the first to go if the strike were to go into the second or third week, says Jason Miller, an associate professor of supply chain management and interim chair of the Department of Supply Chain Management at Michigan State University.

The last time the ILA went on strike was in 1977.