As someone who has never read Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” I found that the play adaptation at the Huntington Theater Company to be a compassionately presented racial trauma.

The show, directed by Awoye Timpo and written by Lydia R. Diamond, will run through March 26.

Amid trauma and racism, Pecola (Hadar Busia-Singleton) has a continuous desire for blue eyes. We learn during her quest in obtaining them that it stems from her mother’s tragic background.

Hadar Busia-Singleton in The Huntington’s production of The Bluest Eye by Lydia R. Diamond.

While the story centers around the young girl, the play makes it a priority to represent the stories of those around Pecola, especially that of Mrs. Breedlove’s (McKenzie Frye), Pecola’s mother.

Timpo was inspired by the storytelling traditions of Black rituals, arranging the seats in a circle surrounding the actors. The stage represents the cross-section of a tree cracked in the center, which became the centerpiece of the show. The cast consists of eight members who take on multiple roles, set in front of minimal stage design: some chairs, a few food props, and a doll representing a white character in an all Black cast.

The stage set-up narrows the audience’s attention on the performers. Audience members had to rely on the power of the performances themselves rather than finding the symbolism with a maximized set.

The cast in The Huntington’s production of The Bluest Eye by Lydia R. Diamond.

Frye’s performance beautifully represented her character’s pain and anger, especially because of her powerful singing, which reverberated against the walls and gave me goosebumps. Her limp, a small detail, characterized a piece of her weakness and her constant battle with racialized beauty standards.

When she describes the racism she experienced while giving birth to Pecola, her performance gave me an emotional understanding of the unfair treatment Black women face during pregnancy. It was something only a theater performance could effectively display. Her chilling moans projected in the room.

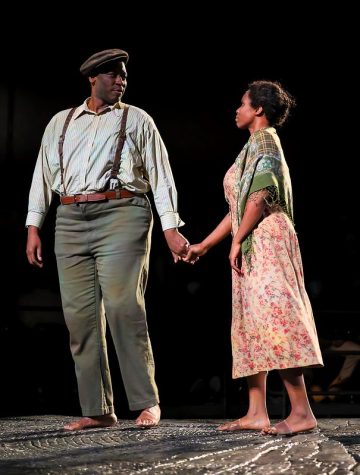

Greg Alverez Reid and McKenzie Frye in The Huntington’s production of The Bluest Eye by Lydia R. Diamond.

Timpo’s direction and Diamond’s screenplay refrained from making heavy scenes from the novel explicit. Cholly’s (Greg Alverez Reid) first sexual experience is interrupted when two white men enforce it. The scene is traumatic and can be overwhelming for any audience to witness, but Timpo and Diamond’s subtle choices made it emotionally powerful while leaving room for enough interpretation from the audience.

At the beginning of the show, Pecola was dressed by the other characters. By the end, she was undressed, symbolizing her loss of innocence after she got pregnant and an ultimate stripping of her identity due to racial trauma.

The show left me with the realization that intergenerational trauma is often the root of racial trauma. It was a beautiful, yet emotional portrayal of the story of a young girl who believes her life would be better with blue eyes—a common belief to those who came before her.