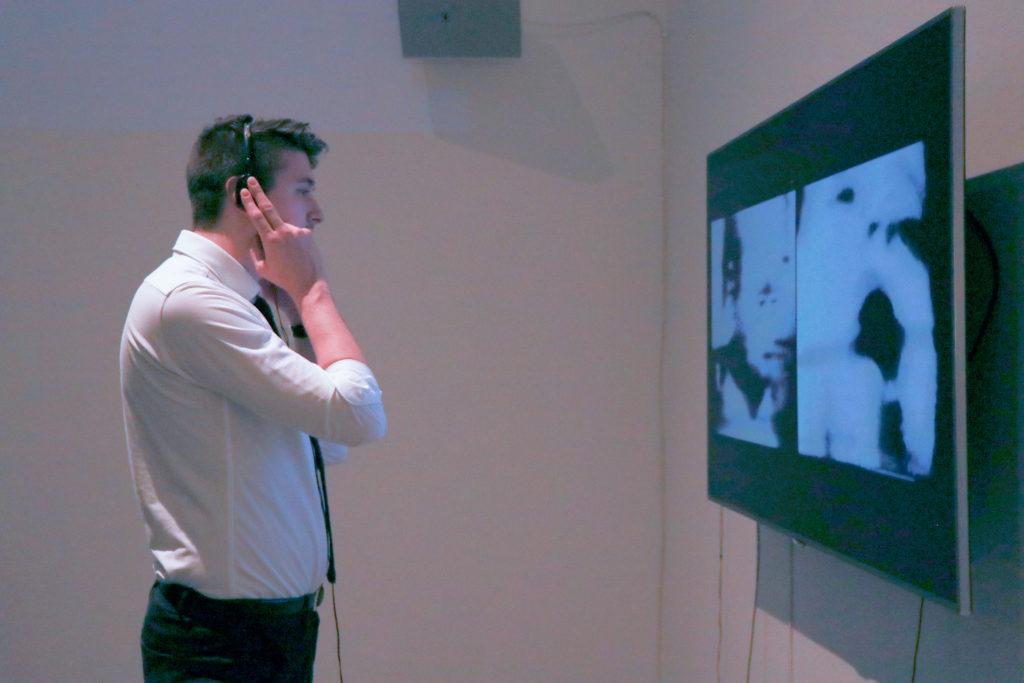

The opening night of “The Vision of Television” exhibit filled the Emerson Media Art Gallery with flashing wall projections of experimental media art, staticky television screens, and an unusual emotional charge on Nov. 15.

Late art historian and curator Joseph D. Ketner II researched archives in Germany for five years to gather the work of avant-garde artists who used broadcast television as a medium for art.

The exhibit was not only the first one of the season, but also the first to follow Ketner’s passing in September.

Freshman Cameron Carleton, a gallery guide, received a packet from his superiors beforehand to study and understand the artwork presented that night.

“In the late 1960s and mid-1970s, this was the new medium of the time,” Carleton said at the event. “This was groundbreaking technology, so a lot of artists kind of took the chance and hoped that television stations would give them air time to air whatever they wanted. They tried to push the boundaries as much as possible.”

“The Vision of Television” runs until Jan. 19 in the Emerson Media Art Gallery, which is open Wednesday through Saturday from 2 to 7 p.m.

James Manning, exhibition manager and Ketner’s long-time friend, helped finish and put together the show after Ketner’s passing. He said the exhibit displays how mid-century artists experimented with mixing art and broadcast.

“There is a lot of pieces that he found, especially in the German archives, that hadn’t been seen since they were aired,” Manning said. “And some of them are very important pieces—there is documentation of the first Fluxus event, and there’s also documentation of one of Joseph Beuys’ most famous performances where he talks to a dead rabbit.”

According to the Tate museum, Fluxus is an active avant-garde collective of artists that engages in experimental art performances since its start in the 1960s.

Ketner’s son, Alex Ketner, attended the exhibit on opening night after following his father’s work for years. He said he witnessed his father discovering the pieces one by one during his travels back and forth from Germany.

“I’ve always loved that about all my dad’s work. Everything he’s ever found, every exhibit he’s ever shown, it’s never been the most popular thing—it’s always been the obscure,” Alex Ketner said. “It’s always been the rare finds.”

George Fifield, director of Boston Cyberarts and Ketner’s friend, stepped in after Ketner’s passing to help finalize the exhibit as well. He wrote the explanatory texts on the kiosks interpreting the pieces displayed.

“A number of people there really felt that it was their responsibility to bring avant-garde culture—not just culture—to the people,” Fifield said in an interview.

Fifield described Ketner’s discoveries of documentaries on avant-garde art in these archives as gems that reveal the overarching interaction between video art and public television stations in Germany and the United States.

“Key to this are these early German documentaries from German television stations that made an effort to go out and make documents about things like the Zero group, things like Joseph Beuys, and present them on air. Some of these shows are being seen for literally the second time ever,” Fifield said.

Fifield urged people to come see the exhibit and learn about these historical gems and said his favorite is “Three Transitions” by Peter Campus, which he refers to as the most perfect piece of video art ever made.

Fifield said he thinks the history of video art has recently grown and people should look at the wealth of information made available to them.

“Anytime I’m sad, I’ll be around here, or anytime I’m happy, whatever. But I’ll come here as much as possible, definitely. And everyone should,” Alex Ketner said. “Everyone should always come here, all the time, this is a little gem that you would never know, right next to the Common.”