A new exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston pays tribute to hip-hop and graffiti culture, displaying it as a testament to the post-graffiti American art movement.

Titled “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation,” the exhibition links the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat to the early days of hip-hop culture, Liz Munsell, the MFA’s Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, said in a press conference on Oct. 19.

The show will run from Oct. 18 to May 16 next year in the Ann and Graham Gund Gallery alongside an illustrated catalogue, including scholarly essays and detailed shots of artworks included in the exhibition.

Out of the 120 pieces in the show, 25 are Basquiat’s work, while the others highlight artists like A-One, ERO, Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Keith Haring, Kool Koor, LA2, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, Rammellzee, and Toxic.

Munsell said this exhibition is crucial to the public discussion about Basquiat and his contemporaries’ involvement in the hip-hop generation, which was neglected by the mainstream art world.

“[The exhibit] was really to show more of [Basquiat’s] intersections with hip-hop culture, but also with intersections with communities of color,” Munsell said.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) was an American artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent who came out of the Neo-expressionism movement of art, which is characterized by extreme subjectivity and abstract utilization of artistic mediums. He started his career making graffiti art in the Lower East Side of Manhattan on the sides of train cars and buildings, then moved to poetry, drawing and painting. He used his art to comment on power dynamics like wealth versus poverty and the reality of being Black in America.

Hip-hop is a multi-disciplinary movement. This includes mediums of music, dance—specifically breakdancing—and graffiti culture. Going back to its conception in the 1980s, the exhibit seeks to break down the history of what is now a worldwide phenomenon.

All of the artists exhibited in the show except for Keith Haring are people of color. Munsell said these fellow artists have not been traditionally included in the narrative around Basquiat and his work.

Greg Tate, author, musician, and founding member of the alternative music organization Black Rock Coalition discussed how the featured artists worked together as creatives—but also as friends, intricitally connecting their personal lives with the art.

“All of these artists hung out on a weekly, nightly basis with each other in the downtown club scene,” Tate said. “We’re really focusing on that moment that’s called post-graffiti, when these artists chose to enter into the galleries to present their work.”

The artwork that is presented is both geographically related and genre-focused. The majority of this work came out of the East Village and West Village of New York City, where the movement was centered, Tate said.

“[The artists] ended up experimenting with different mediums and cross-pollinating these different scenes at the same time,” Tate said. “A lot of other kids were coming from the boroughs to this epicenter, because it was the place to be.”

This cultural shift took place in a version of New York City that already had an established gallery scene, due to what Tate called a “useful audacity” to interject ideas into a culture dominated by white artists.

The MFA took three years to plan the show due to the large institutional nature of the museum. The curatorial team worked to ensure the exhibit presented a sense of authenticity, Munsell said.

The wall texts, presented in English, are available also in Spanish and Haitian Creole—reflecting the artists’ multilingual identities—through the MFA mobile app.

“The idea behind that is that Jean-Michel is often referred to as a Black artist, which he absolutely was, but he was also Latinx,” Munsell said. “It’s really important to recognize that artists of color have not received enough space in our institution.”

In 2019, the MFA faced allegations that middle schools visiting the museum were subjected to racial insults during a field trip.

This language accessibility and representation also incorporates the public face of hip-hop in America as a contribution from Black culture, Tate said.

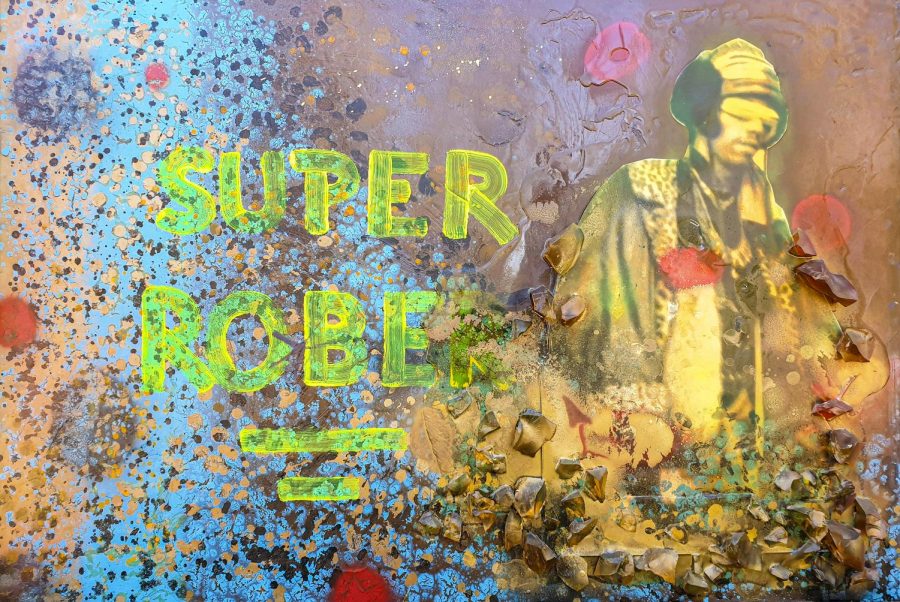

Return of God to Africa, 1984, Fab 5 Freddy. All rights reserved, Fred Brathwaite. (Media: Courtesy of the Museum of the Fine Arts)

The MFA’s community outreach program included a group of local, contemporary hip-hop artists into the conversation around this exhibit to see how the show sat with them. This was an opportunity for the MFA to speak to these communities who are historically and systemically left out of institutional conversations, as well as an opportunity for those communities to speak back, Tate said.

“They were amazed that the MFA was even doing this show,” Tate said. “It was very important for the director of the museum that Boston had a voice in the show—that’s why the wall text will have voices from those individual communities.”

The exhibition also includes a playlist curated by Tate with songs directly inspired by artwork in the show and out of the post-graffiti movement as a whole, like “All of Me” by Billie Holiday and “Rebel Without a Pause” by Public Enemy.

The diverse nature of the exhibition works to encapsulate the complexities of this American movement in a modern world where cultural institutions are facing challenges due to COVID-19.

“Despite the threats and complete lack of support for young artists, they were so resilient and persistent,” Munsell said. “It’s a real lesson in times of hardship, like right now, for young artists to see this show and hopefully draw inspiration from it.”