When you ask someone why May 4 is significant, they might say it’s about honoring rebels who stood up to an imperialist empire. While that isn’t entirely wrong, the day has nothing to do with Star Wars. The day memorializes something far more impactful in American history.

This May will mark 55 years since four college students were killed, and nine more injured, at Kent State University in Ohio. An anti-war protest was taking place on the campus when the National Guard arrived after reports of a campus building being set on fire to protest injustices happening at the hands of U.S. military presence in Vietnam. As the guardsmen made their retreat, they spontaneously turned 180 degrees to a group of students in the parking lot, and opened fire for 13 seconds straight. Student journalist John Filo captured the moment twenty-year-old Jeffrey Glenn Miller died after being shot in the head. Knelt above him was student Mary Vecchio, whose look of horror is now forever immortalized in what came to be known as one of the most memorable photographs from the past century.

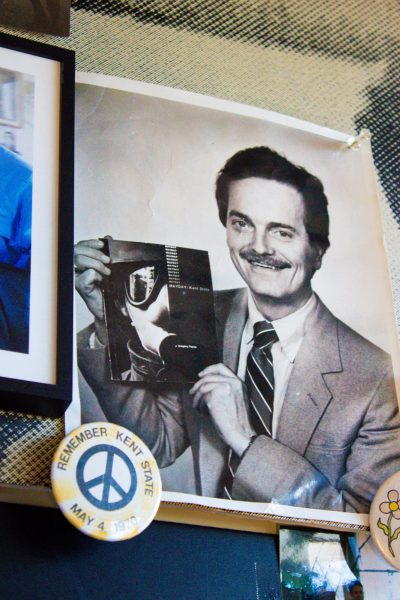

Gregory Payne, chair of the communication studies department, has dedicated his life’s work to paying homage to the victims of the Kent State massacre. His requiems come in many forms—doctoral dissertations, books, plays, and movies. A tapestry of Filo’s image hangs in his office, along with mementos of every kind.

“Many people would say that [Kent State] was the beginning of the end of the war in Vietnam,” he said.

Maybe it’s the shot’s composition, how the foreground and background are balanced by bereaved students. Or Vecchio’s twisted face over Miller’s decimated body, which some have likened to The Pieta—the biblical, tragic image of the Madonna cradling her son the Savior’s dead body.

Emotion fills Payne’s eyes when he talks about his play that brought Vecchio and Miller’s mother together for the first time. She wanted to know he didn’t suffer in his final moments, and thanked her for being by his side. It was also Vecchio’s first time returning to the site of the massacre. Though Payne wasn’t there with her at Kent State on May 4, the scene is still “indelible” for him—and he isn’t alone in that sentiment.

“It’s an open wound that still festers,” he said.

Perhaps what makes it linger in the mind of Americans, and why it caused such outrage at the time—400 colleges and universities across the country subsequently cancelled classes and sent students home—is the idea of the U.S. government slaughtering four white kids in Ohio, in Payne’s mind. The country had killed four of their own. The war had come home.

Some cynical adults at the time questioned why the students in the photograph were protesting the war in the first place. As recent as 2021, the Washington Post ran a piece on that iconic photograph, and many of the almost 4,000 comments were filled with spitfire arguments about whether it was staged, whether they deserved it, or whether it was the CIA.

So what was at the root of youth outrage over the Vietnam War? It wasn’t even on U.S. soil, after all. But the blood spilled was American.

Payne recalls the night he had a brush with the draft. He was no stranger to how the toils of the war in Vietnam afflicted those on home turf, too. He watched as boys from his childhood in southern Illinois answered the call, some of whom didn’t come home.

The draft was a bit of a lottery. The process of calling upon random young boys was not unlike how one would call numbers for bingo, if bingo night were far more macabre. Payne remembers how the first ball drawn corresponded to months of the year. September. The next ball indicates a date in September, and any birthdays on or before that day must go to war. September 17. Payne breathed a sigh of relief. He was born on the 18th.

Others were not so lucky. The carnage from Vietnam is still felt today—and it is felt by more than just Americans. As many as 2 million Vietnamese civilians are estimated to have been killed, with a million more North Vietnamese fighters dying, and over 200,000 South Vietnamese. Two thirds of military personnel who came back from the war alive suffered from disabilities that will follow them the rest of their lives. They’re also 23 times more likely to suffer from extreme mental health problems, like PTSD and suicidality. 23,000 American veterans committed suicide upon discharge from service in Vietnam. This is not to mention the countless health complications from Agent Orange, a tactical herbicide used by the U.S. military on vegetation and foliage in Vietnam during the war, including diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and more. This affected not just U.S. soldiers, but Vietnamese civilians too.

It’s hard to say whether the youth of the 60s would’ve mobilized had their peers not been drafted, but Payne doesn’t waste time on what-ifs. And neither does John Bach, a local Boston organizer who spent three years in federal prison for dodging the draft.

“I came of age during the height of the civil rights movement,” Bach said. “I learned something about being engaged in the burning issues of the day. That led seamlessly into the anti-war movement.”

As a sophomore at Wesleyan University at the time, Bach was safe from being drafted because of his student deferment. This did not deter him, however, from taking a stand against the war—what he calls “an obligation to resist.” With tears in his eyes, he told me those three years behind bars were the freest years of his life.

“Freedom does not depend on what side of the prison wall you’re on, it depends to what extent you’re able to serve your fellow inmate, your brothers, brothers and sisters, the way that you’re able to serve your community,” he said. “And that is the guarantee that you can never be imprisoned.”

Bach served the second longest sentence of anyone incarcerated for draft dodging during Vietnam. He called it a “magnificent illumination,” where he learned the meaning of life:

“To be loved well, and serve others,” he said. “That’s the immunization of being disaffected and alienated.”

Today, Bach says the volume of Palestinian lives lost in the historic conflict between Israel and Hamas reminds him of back then. The current death toll is 48,000 Palestinians and 1,200 Israelis.

Bach uses his voice and platform by speaking at rallies. He is also the Quaker chaplain at Harvard University where, through his faith, he engages with his community to fight for peace and social justice.

Every May, 77,000 daffodils bloom on Kent State’s hillside, one for every American life lost overseas. And if it weren’t for Filo’s famous photograph of the Kent State tragedy, and the four American lives lost in Ohio, that number might have been far higher.

Payne calls May 4 the day of reckoning, where the American people had to reckon with a senseless war their tax dollars were funding, fought by their sons and nephews and cousins. To him, the image of Vecchio and Miller is a “metaphor for the entire period.” If a picture is worth a thousand words, that one’s worth millions.

Bach led an exercise at an encampment for Palestine in Cambridge, where he spoke directly to students. He begins his recollection of what he said that day.

He begins,“so what I am going to do [is] I’ve enumerated 22 images from my life [that] have made me who I am today…When I’m done with these 22 [images], I’m going to ask you to quickly pick two other people you’re sitting around and form a triad. We’re going to be quiet for a minute….during that that minute of silence, see what images from your past come into your mind that have brought you here today, and share that with the other two people.”

Along the image from Kent State was a Vietnamese Buddhist monk who self-immolated and a Vietnamese girl running from a mushroom cloud of napalm.

“All the talks were impassioned and beautiful and good and cognitive and needed, but it was just one talking body after another,” Bach recalled. “It’s a wonderful way of building community, and to share that sense of sorrow for what we’re responsible for. If I may say so myself, it’s a good idea. Plagiarize it.”

The image from the Kent State massacre did not mark the end of civil unrest among American youth, nor did it mark the beginning. What it marked was the end of a decade besieged by violence, in Vietnam and beyond—including a series of consequential assassinations, like those of President John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., or Robert F. Kennedy.

“That was a real trauma for a whole generation of people like me,” Payne said. As a young politically-engaged individual, he was on the campaign trail with Bobby when he was assassinated.

The turn of the decade into the 70s also marked the beginning of a new era for America, one presided over by President Richard Nixon. For all his ethical blind spots, Payne notes, the disgraced former president still resigned after Watergate.

“We’re only as good as the people we elect,” he says, warning of leaders “drunk on their own hubris.” After all, those who erase history are bound to repeat it.

Payne recounts an old adage from Franz Kafka, whose book was gifted to him from a teacher who advised him during the crafting of his doctorate. The book implores the reader to look to the past in order to not relive it in the future—and to pass the torch to the next generation.

“The advice I’d give to you is, stand up for what you believe in,” he said. “You’ve got to trust your own anchor.”

Bach’s recommendations for young people who struggle with fatigue from all the political issues of our modern day is to “not let the bastards grind you down.”

While there are more differences between the anti-war movement among youth today, (“there are very few of your colleagues who are coming back in body bags,” Bach said), and that of the 60s, the spirit and fervor of college students to dream of a world better than this one is a common thread, according to those who lived through both movements.

Payne sees a “disruptive creativity” in Gen Z amongst the idealism, positivity, and dissatisfaction with the status quo. “It’s a terrible burden that young people have,” he says, in reference to the current state of our world and country. But he is optimistic about one thing: “There is goodness that will prevail.”