Sept. 11, 2001 began like any other day for Elyse Van Breemen. Then she received a phone call she would never forget.

“I didn’t believe it,” said Van Breemen, older sister of former Emerson Professor Myra Aronson, who died in the terrorist attacks. “I did hear about it on the radio and thought, ‘This is some kind of 1984 joke or something,’ and I went back to work. Then I got a call from my other sister’s boyfriend who said, ‘We think Myra was on the first plane.’”

Prof. Myra Aaronson, who died on United Airlines Flight 175

Aronson, 50, was a passenger on United Airlines Flight 175, which departed from Boston’s Logan Airport that morning. The flight was en route to Los Angeles before it was hijacked and crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. In addition to her role as a public relations manager at a software company in Cambridge, Mass., she taught public relations courses as an adjunct professor at Emerson.

Aronson was one out of the 2,977 victims in the attacks, but she is also part of a much smaller group, as one of only three Emerson community members killed that day. The two other victims of the attack, alumna Jane Simpkin ‘88 and Sonia Mercedes Morales Puopolo—who both died when their planes hit the towers. Puopolo was the wife of an Emerson Trustee, Dominic Puopolo, and mother of alumna Sonia Tita Puoplo ‘96. Simpkin worked in music management at the time of her death.

The younger Puopolo, now an affiliated faculty member in the communication studies department, remembers her mother as “an incredible bright light.”

“My mother was my best friend,” she said in a Zoom interview, her late mother’s wedding ring adorning her pinky. “We were very close. We were inseparable.”

Morales Puopolo was aboard American Airlines Flight 11, the first plane to be hijacked that fateful September morning—just a few seats away from Mohamed Atta, the plane’s lead hijacker. Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m.

Her family—like the rest of the world—remained in the dark as conflicting information began to trickle in from New York.

Puopolo said she and her father raced to Logan Airport after they received a phone call letting them know there was a “problem” with her mother’s flight. In the days before the attacks, and even the morning of, as loved ones boarded doomed flights, the thought of a plane being hijacked to act as a weapon of mass destruction was the furthest thing from the minds of those who would later lose so much.

“We couldn’t fathom that someone could use the plane as a missile,” she said.

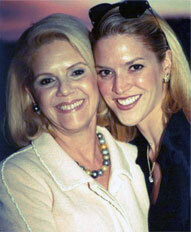

Sonia Tita Puopolo (right) and her mother

Once Puopolo learned the truth about her mother’s flight, she was devastated. She couldn’t comprehend who would have deliberately caused such an unimaginable tragedy—and why someone would have taken away her mother.

“There was tremendous confusion about who did it,” she said. “We wondered, ‘Why did they hate us so much?’ We thought maybe the world was ending.”

“The world did end for some of us,” she added, soberly.

As the U.S. reeled in the days following the attacks, the Emerson community also counted its losses. The college held a vigil to commemorate its victims, and provide emotional support for those left behind.

Van Breemen, the sister of one of the victims, admitted that she wasn’t especially close to Aronson in adulthood. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the attacks, she committed herself to memorializing her younger sister—crafting a booklet full of reflections from Aronson’s family and friends.

“I talked with Myra the night before her death,” wrote Betty Murray, a friend of Aronson’s, in the booklet. “It wasn’t an important conversation; she just wanted to know how my poison ivy was. Therefore, what I’ll remember most about Myra was her concern, and interest in the people with whom she came in contact.”

“Myra was much more than my aunt,” wrote Aronson’s niece, Karen. “She was my very first babysitter, she gave me my first pair of Levis, and turned me on to the Monkees. And she never missed a birthday. I felt such a sense of relief being with Myra. She was my family, but treated me like the adult I thought I was.”

A year after the attacks, Puopolo’s mother’s wedding ring was found under 1.7 million tons of rubble at Ground Zero. Twenty years later, she said the moment the ring was returned to her family made her believe that “miracles do happen.”

Simpkin’s family could not be reached for comment on this article.