On Sept. 6, 2001, sophomore journalism major Cyndi Roy was writing about first-year orientation and college dorm policy. She never imagined that, just a few days later, she would be crying in the newsroom hallway, reeling from the deadliest terrorist attacks in the history of the globe.

“That was the day the world changed,” she said. “I don’t think I could have, at that age, even acknowledged that I felt that way—but it was earth-shattering.”

Roy, now Cyndi Gonzalez, was one of several dozen Beacon staffers gathered in the newsroom on Sept. 11, as reports of the calamity in New York—and in Washington D.C., and Pennsylvania—streamed in on television. Despite The Beacon’s commitment to administrative and campus life coverage, few expected to ever tackle anything as shocking and catastrophic as the events of that devastating Tuesday morning.

In fact, Gonzalez hadn’t thought much of the news of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center. She turned off Good Morning America and left in time to catch the train for her first Tuesday class.

“I thought it was really odd,” she said. “Honestly, I thought it was some kind of freak accident.”

Meanwhile, The Beacon’s editor-in-chief, junior journalism major Marc Fantasia, was sitting in a class taught by Professor Michael Brown when he first heard the news of a plane hitting the North Tower.

“I don’t think anybody really comprehended what that meant,” Fantasia said. “We were huddling around, trying to figure out what’s going on. Then someone walked by and said ‘What are you doing?’ Mike Brown just said he was having class. ‘We’re abandoning the building,’ they said, ‘Class is over, you have to leave right now.’”

Once classes were canceled across Emerson’s campus, students quickly realized the gravity of the situation—as Gonzalez recalled, word-of-mouth soon revealed it to be a “much bigger deal” than what she had initially assumed.

“Everybody pulled out their little flip phones and tried calling loved ones, and we couldn’t get through because all the cell towers were overloaded,” she said. “As fellow Beacon reporters and students, we just found each other and gathered in the Beacon offices to figure out what we needed to do.”

Fantasia walked into The Beacon newsroom just as the first tower, the South Tower, collapsed on the television, and the horror of what was happening struck.

“It’s like, ‘holy shit,’” he said.

***

Despite the initial shock of the attacks, junior journalism major Brian Eastwood said the newsroom quickly accepted their responsibility as journalists to cover the events shaking the nation.

“We all tried to pick a little bit of what was going on to focus on,” Eastwood said. “It wasn’t going to fall on one person’s shoulders to write all the 9/11 coverage. We had everybody do a little bit.”

As editor-in-chief, Fantasia began doling out assignments to the staff writers present. One team of reporters went to Boston’s Logan International Airport after it emerged that two of the four flights had departed from there—a choice which Eastwood described as “probably not the best idea” in retrospect, given the security concerns.

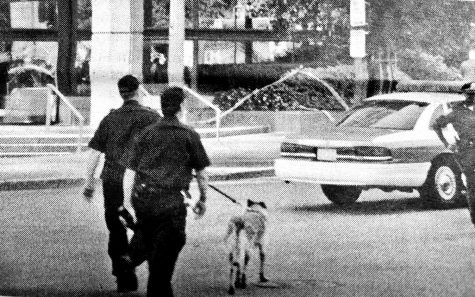

A BPD dog team outside the Copley Westin Hotel, which was believed to be occupied by potential terrorists

The editor-in-chief himself, along with Managing Editor Amanda Lehmert, went to the Westin Hotel in Copley Square. According to Fantasia, a picture he snapped of FBI agents storming the upper floors in search of a potential suspect was later picked up by the Associated Press.

For some staff members—including one New Yorker, who had grown up in lower Manhattan—it was hard to cope with the trauma the nation was going through.

“We were just giving people an ear, someone to listen,” Eastwood said. “Letting them express their feelings and helping them deal with what they were going through.”

On the other hand, Gonzalez said that working in the newsroom through the first day actually helped her, at least for a time, distance herself from the tragedy.

“It was such a traumatic event—but, you know, we had a job to do,” she said. “Actually, in some ways, it was very nice to be able to do a job, to do something important and relevant—and not just sit in front of the TV and have to watch it over and over and over again.”

Fantasia recalled the surreal experience of working tirelessly on Sept. 13’s print edition—only two days removed from the attacks—while the streets of Boston were empty and the country was in mourning.

“I don’t think we actually processed what was happening until much later,” he said. “That day, we didn’t really know what to think. It was something that had never happened before, that was unprecedented.”

“Cindy interviewing the daughter that night was probably when, at least for me, it kind of hit,” he added.

***

To this day, Gonzalez remembers that interview as the hardest she would ever have to do.

“I can’t recall how, but we got word that Sonia Puopolo [wife of Emerson trustee Dominic Puopolo] had passed away,” Gonzalez said. “She was on one of the planes, and her family was very involved with Emerson.”

Fantasia assigned the interview with Sonia Tita Puopolo, daughter of the elder Puopolo who had graduated from Emerson in 1996, to the sophomore news editor.

“I think what he sensed was that I could do it in a way that was compassionate, but also [understood] the story,” she said.

In a short phone interview on Wednesday evening, Gonzalez asked Puopolo—only a few years her senior—about her mother who had died with thousands of others in New York.

“I remember her crying,” she said. “At one point, she was asking me to tell her that this hadn’t happened, that it wasn’t real. And, you know, I’m a young college student, trying to process this on my own.”

“I remember trying to put on a brave face—and the second I got off the phone, just bawling,” she continued. “I just burst out into tears and then couldn’t stop.”

***

Sonia Mercedes Morales Puopolo was among the three Emerson community members memorialized in the Sept. 13 edition of The Berkeley Beacon.

“Some members of the Emerson community will remember Sept. 11 as the day they first felt terror,” read the article’s lede. “For one Emerson family, it will be remembered as the day they lost a wife, a mother, and a friend.”

“It is one of the most significant memories of my time at Emerson,” Gonzalez said. “I’m so grateful I was a part of The Beacon then—I had a support group, a community to belong to.”

By the end of the week, the paper’s staff was, in Gonzalez’s words, “emotionally exhausted”—yet she still found the work that she did important.

“This idea that, because you’re a reporter or a police officer or a firefighter, you should do your job without any [emotional] recognition is the completely wrong way to go about it,” she said. “Allowing yourself to be vulnerable and letting your interviewees see you as human is important. It’s important for reporters to go get the story—certainly ask the tough questions—but also to show compassion.”

“It’s actually a really wonderful life lesson that reporters have a job to do, but they’re also incredibly human,” she said. “That’s what makes the best reporters—those who have that ability to emphasize and be compassionate while also doing the job, getting the story, sharing the story.”

“I think the reason Sonia was willing to share her story was because her mother deserves to have her story told,” she said. “For that, I’m still very grateful, 20 years later.”