The Emerson Prison Initiative is set to resume in-person instruction for incarcerated students at the Massachusetts Correctional Institute in Concord on April 5 after access to the prison was halted twice due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The program—which provides an Emerson College education to incarcerated students at the medium-security prison—switched to asynchronous instruction during the spring 2020 semester when the pandemic first hit Massachusetts. After briefly transitioning back to in-person instruction at the start of the fall semester, it again became asynchronous in late November when MCI-Concord reported 159 positive COVID-19 tests—the highest number among incarcerated people in the state—according to WBUR. As of March 22, there are 438 incarcerated people housed at the men’s state-run prison, according to the Massachusetts Department of Corrections.

Founder and Director of Emerson Prison Initiative Mneesha Gellman said the goal of EPI throughout the pandemic has been to follow through on their promise that students enrolled in the program are receiving the same quality of education as students on the Boston campus.

“We’ve had to find ways to ensure that quality,” Gellman said. “We put tremendous detail into making sure the [in-person] contact hours are what they should be and that the time for the work is suitable for what’s required. With that level of commitment, we’ve been able to adjust the academic calendar.”

The EPI program was founded in 2016 at MCI-Concord—a 40-minute drive from Emerson’s Boston campus. In the fall of 2017, 20 students from MCI-Concord were admitted into the EPI program, and in 2018 the college began officially offering students a full degree-seeking program. The five-step admissions process is intensive, with a timed essay exam and interview. Only 20 out of nearly 100 applicants were accepted in the first cohort, 12 of whom are still currently enrolled.

Students are enrolled in a group Interdisciplinary Studies major hosted through the Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies, and graduate with a bachelor’s degree in Media, Literature and Culture after five years of study. The EPI program was modeled off of the Bard Prison Initiative, founded at Bard College in 1999.

“For students who will be graduating and then shortly afterwards released back into society, changing from incarcerated people to returning citizens, the impact there is that they will be qualified for a range of jobs that they were not qualified for before and that’s going to totally change what their reentry scenario is,” Gellman said. “For students who will continue to be incarcerated post graduation, they are the next intellectual leaders within the facilities where they’ll be able to set the values of the community in ways that are more productive and more intellectual than what was happening previously.”

The start of the spring 2021 semester was pushed back by the Massachusetts DOC from its original Jan. 1 start date to March 1, and then again to April 5, according to Gellman.

“We would have started as soon as the majority of people incarcerated at MCI-Concord had received the second dose of the vaccine, which took place at the end of February,” Gellman said. “We are only allowed to operate at MCI-Concord at the invitation of the Department of Corrections; when they fix timelines, we don’t have a lot of say in changing them—even if they don’t always serve our academic purposes as best as we would like.”

Mneesha Gellman and Lee Pelton

The adjusted timeline forced the structure of the spring semester to mirror that of a summer session. The intensive academic schedule will require faculty members to hold twice-weekly classes for seven weeks, instead of the originally planned 14-week semester with once-a-week classes.

“Students rely on some time during their day for other things that they’re involved in [besides EPI]—their prison industry jobs, visits with family, phone calls, other enrichment programs they might be a part of—so it is a big demand both on faculty and students,” Gellman said. “But it will allow us to complete both spring classes in April and May, and then also run our summer classes intensively in June and August.”

Another cohort of students was slated to be admitted to the initiative last summer, but plans were spiked when the pandemic struck. Approximately 15 new students will be enrolled this summer to begin their path to obtaining a bachelor’s degree, Gellman said.

A study conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics between 2005 and 2010 found 67.8 percent of the 404,638 incarcerated people surveyed would be rearrested within three years after their release. However, for incarcerated people who obtain a bachelor’s degree, the likelihood of recidivism falls to 5.6 percent, according to Zoukis Consulting Group, which runs a federal prison consulting team.

Incarcerated students at MCI-Concord do not have access to the internet, which EPI Coordinator Cara Moyer-Duncan said proved to be a challenge when the program was forced to operate asynchronously during the pandemic. EPI was granted approval from the DOC to mail educational packets through the U.S. Postal Service for students to complete to accommodate the asynchronous format.

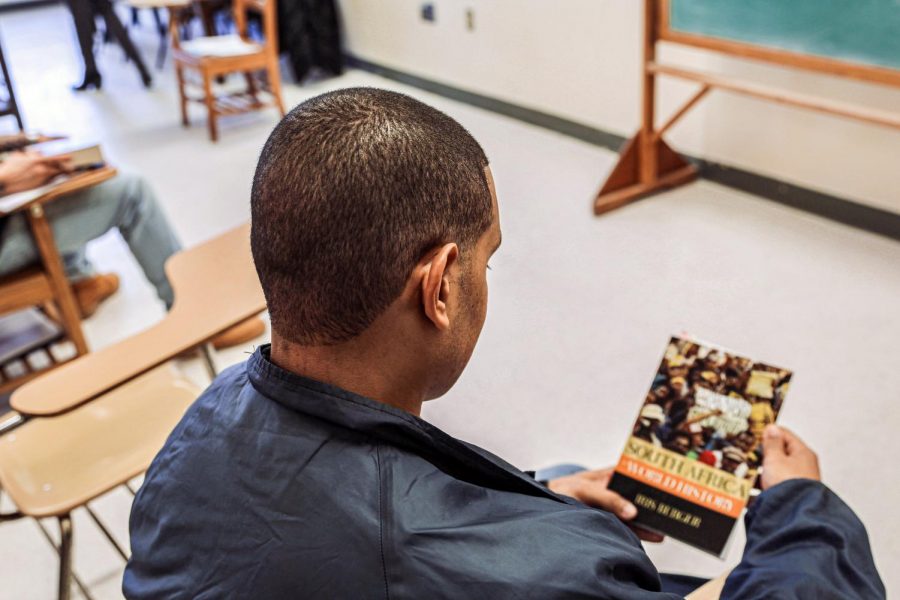

Students in the program

“Where traditional students at the Boston campus can benefit from the flex learning plan, the hybrid model and enjoy a wealth of information—from recorded lectures to films, etcetera—available on Canvas, we have to provide asynchronous instructional content via analog packets, actual paper to students,” Gellman said.

Moyer-Duncan said one of her responsibilities throughout the pandemic has been sending academic materials to students and then collecting it through the mail once they send back their completed work.

“Students would send us letters if they have questions about the materials, or just to let us know how they’re doing or give us an update on what’s going on,” Moyer-Duncan said. “When we start in April, the first week of classes is going to be finishing up the fall semester.”

The New England Commission of Higher Education requires all Emerson classes to have a total of 47 contact hours per semester. On Emerson’s Boston campus, half of those hours have been conducted remotely. But, EPI students are required to have 37 hours of in-person instruction and are only allowed 10 hours of remote learning per course, according to Moyer-Duncan.

Gellman said the first cohort of students enrolled in EPI is set to graduate in July or August of 2022 if the pandemic no longer interferes with plans for the program.

“We have been receiving communication from students throughout the pandemic and most of them say, ‘We can’t wait to return to the classroom, please bring the college programs back in,’” Gellman said. “One of the impacts of the pandemic on incarcerated people in Massachusetts and many other states is that they’ve been restricted the majority of time to their cells.”

Before the pandemic, incarcerated people at MCI-Concord were allowed out of their cells multiple times a day to take phone calls, see visitors, and participate in recreational time. Since the pandemic, the Massachusetts DOC has limited internal movement, requiring incarcerated people to remain in their cells for up to 23 and a half hours each day, Gellman said.

“For an entire year now, our students have been existing in a very abnormal situation in an already abnormal environment,” Gellman said. “One of the biggest challenges I think we have in returning to instruction on April 5 is just recognizing the degree of trauma that students are operating with.”

To prepare faculty members to teach at MCI-Concord in the spring semester, the initiative hosted an invitation-only workshop on March 25 with a specialist in trauma from McLean Hospital to teach professors about trauma-informed care when interacting with incarcerated students.

“The conditions have been very, very difficult for all incarcerated people including our students,” Moyer-Duncan, who is also a professor at the college, said. “Some of our EPI students [had] COVID. That is difficult under the best of circumstances, and even more challenging in the carceral context, to be really sick. On top of that, they’ve had family members or people who they love who are really close to them, who have been affected by the pandemic. They’ve lost loved ones to COVID-19 and of course they’re inside and so they’re not able to be with their family or to go to funerals or to grieve in that way.”

Emerson Prison Initiative staff and staff from MCI-Concord

Only 12 of the original 20 students that were initially welcomed into the EPI program in 2017 are still currently enrolled, Gellman said.

“The Massachusetts Department of Corrections moves people around through the facilities,” Gellman said. “We’ve only had a few students actually released from prison, but other ones have been moved at the discretion of the Department of Corrections, so we currently have 12 continuing at MCI-Concord.”

Students who are moved from medium security MCI-Concord to a minimum security prison are no longer eligible to complete their degree through EPI—a result of DOC policies, according to Gellman. Last year, EPI petitioned to offer classes at a minimum security prison in Concord, which was denied by the DOC. Gellman said EPI is applying for access again this year, and is always looking for ways to expand the program.

“This past fall we ran a lecture series with Emerson faculty going inside [Suffolk County Jail] and talking about their disciplines with incarcerated students there,” Moyer-Duncan said.

Emerson faculty who teach in EPI receive a $5,000 honorarium on top of their salaries, Professor and Dean of Liberal Arts Amy Ansell said. Along with Emerson faculty members, professors from Clarke University and Brandeis University partnered to teach classes to incarcerated students at MCI-Concord through EPI.

Along with serving as dean of the program, Ansell also taught a class called “Race and Ethnicity: The Key Concepts” for the EPI program prior to the pandemic.

“It’s tremendously unnerving to be in that context in terms of entering and exiting the buildings and getting materials cleared,” Ansell said. “But once in the classroom with the students, I was just a professor, they were the students, and somehow all of that fell away.”

Writing, literature, and publishing professor Stephen Shane taught a Research Writing course for EPI during fall of 2019. He said the opportunity was humbling.

“Emerson is often trying to think of itself as connected to communities around the city of Boston,” Shane said. “Connecting with a student population like those at MCI-Concord, you are connecting with some of the most vulnerable student populations and students who really deeply value education in ways that I think a lot of other students take for granted.”

The experience of teaching in a prison was vastly different from teaching in an average Emerson classroom, Shane said.

“It looks dystopian—it’s kind of a brutal setting, and I’m not saying I felt brutalized in any way there, but it’s a place that’s meant to look intimidating,” he said. “We sit in a circle like we would in a normal Emerson classroom but you are under constant surveillance. You can close the door, but there are guards constantly poking their heads in and even just watching through the glass. There’s a very minimal sense of privacy to the classroom community, but that’s something that probably takes instructors longer to get used to than it does the students.”

Shane said he asked students enrolled in the EPI program to write profiles about a person, community, or place. The carceral setting limits access outside the prison forcing Shane’s students to be creative about what they chose to write about.

“One student did a lot of research on the middle school that they attended in rural Massachusetts, and they did a lot of research in terms of the economics of that town in particular,” Shane said. “Another person in class chose to profile a space within MCI-Concord, so they profiled the phone booths, where it’s one of the few means of communication incarcerated people have.”

To find research materials, students in Shane’s class were required to browse the limited library within the prison, as well as from a JSTOR database that would allow them to access only abstracts of articles. After his students found material they wanted to use, he would find the entire article on Emerson’s databases and bring them back to class for his students to use.

Students in the program

“[They had to] be creative in really unexpected ways, ways that I think opened up the doors to different types of reading and research, incredible projects that I haven’t seen before in other Emerson classes,” Shane said.

Since teaching his course, Shane said he has not been able to stay in contact with any of his former students due to state prison protocols set by the DOC, which prevent any communication between faculty and students even after students are put on parole and reenter society.

Along with Emerson faculty, students have been able to get involved in the initiative through its interdisciplinary co-curricular course. Students in the co-curricular can receive one non-tuition credit a semester by participating in a Zoom meeting every two weeks.

“50 percent of the time, students are learning about issues related to mass incarceration or college in prison or the pandemic in prison,” Moyer-Duncan said. “And then the other part of the co-curricular they’re actually doing projects to benefit EPI.”

Shane said he hopes to continue participating in the EPI program in the future.

“They are some of the best students Emerson has,” Shane said. “These students are the most driven I’ve ever had in a class as a whole. They’re deeply dedicated to this, so I would very much welcome the chance to teach another [EPI] class.”

Correction: A quote containing incorrect information about faculty-student communication has been removed from this article. This article has also been updated to include that the photos are from the Department of Corrections.