Two exhibitions currently on display at the Institute of Contemporary Art provide viewers with a unique and bleeding edge experience, as they call current ideas of race, culture and personal identity into question.

The “2021 James and Audrey Foster Prize” exhibit and “Raúl de Nieves: The Treasure House of Memory”––both opened on Sept. 1–– and will close on Jan. 30, 2022 and July 24, 2022, respectively.

The Foster Prize exhibit is the ICA’s bi-annual exhibition featuring the work of three Boston-area artists—Marlon Forrester, Eben Haines, and Dell Marie Hamilton. The Treasure House of Memory exhibit is composed of artwork by Raúl de Nieves.

Each of the artists’ work in the Foster Prize exhibit was developed during COVID-19. The art reflects issues relating to race, housing inequality, and the formation of personal relationships, all of which have been brought to the forefront as the world faces a health crisis.

ICA gallery operator Kayla Scullin said this year’s exhibit has a different feel than the previous year.

“A lot of it has to do with the art people are creating during the pandemic,” which oftentimes strives to illuminate the ever present social issues that have become more clear during the pandemic, Scullin said.

Forrester’s work, If Saints Could Fly, consists of four large oil, acrylic, and gold leaf paintings, all depicting Black men throughout history. Each painting features a front-facing, flat and full-body figure with geometric shapes of a basketball court in the background.

“If Saints Could Fly” by Marlon Forrester

The Black male body is at the center of Forrester’s work, depicting both historical and contemporary Black figures as saints.

In his work, Forrester includes Jesus Christ, former President Barack Obama, Haitian-American artist Micheal-Jean Basquiat, Trinidadian musician The Mighty Sparrow, Trayvon Martin, and George Floyd.

Born in Georgetown, Guyana, Forrester’s cultural background and influences inspire his art. The Ethiopian Church, Guyana’s colonial history, the architecture of a Dutch fortress, and elements of Queen Elizabeth II’s crown are integrated throughout Forrester’s work.

“It’s a lot of personal work for [Forrester],” Lindsey Flickenger, an ICA visitor assistant said.

In each of his paintings, Forrester uses bold, Tiffany blue geometric shapes to illustrate a basketball court in the background. Such a unique background surrounding the portraits stands out, perplexing one’s eyes as they trace the geometric maze.

Forrester’s allusion to the sport through the depiction of these shapes solidifies his themes relating to Black identity.

As Forrester’s art works to combat the marginalization of Black individuals throughout history, his use of bold blue, gold, and red colors depict the Black male body in a way that evokes a celebratory feeling.

The intricacies of his work push one to understand how his use of bold colors and overlapping shapes represent a deeper meaning relating to the intersectionality of Black identity, especially as the painted figures take a similar pose to saints and biblical sculptures on display at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres in France. Forrester replaces these religious white figures with Black individuals who did not receive similar recognition throughout history.

Boston born artist Eben Haines’ installation, “Facades,” is displayed in a room adjacent to Forrester’s. “Facades” is designed as a stage set that integrates styles of New England architecture, including weathered teal colored walls and a gable roof. Haines’ work elicits themes relating to home, the passage of time, and structures of power.

Haines’ stage set holds a mysterious and dominant grip over the dimly lit room.

“Facades” by Eben Haines comments on corruption, power, and more.

Burning and extinguished candle sticks are seen throughout his work signifying that time is passing or running out. The addition of weathered domestic furniture, both as physical pieces throughout the set and integrated into the paintings, builds upon his ideas relating to the concept of home and shelter and how it can warp with time.

Haines’ inclusion of dominant appearing head sculptures in his paintings, such as the Forbes Augustus—Rome’s first emperor—and the Nelson Head—resembling ancient Roman war hero, Ares Ludovoski—speak on the corruption of unchecked power.

Scullin said “Facades” is centered around “contemplating what home is” and has a “connection to the pandemic,” as COVID-19 has highlighted necessities, comforts, and obstacles found within the home.

Decorated with oil paintings on canvas, some walls of the set depict New England pastoral landscapes paired with inviting shades of green. Many landscapes include comets streaking across dark grey skies, giving his paintings an uncanny feeling, while other paintings depict unidentifiable bodies draped in cloth sitting around a dining table.

Haines incorporates rich details and color into his paintings, making them appear exceptionally realistic, and his works evoke conflicting feelings of comfort found within the home and the powerful danger of a shelter’s impermanence.

Such feelings are particularly contrasted in the large oil painting titled “As the Rent Rises.” The painting, propped on a chair, depicts a levitating body covered in a flag displaying the abandoned building symbol—a large white “X” on a bright red background, creating feelings of mystery as the levitating and seemingly endangered, possibly deceased body, floats in front of an inviting-looking pasture with trees in the distance.

In the next room over, Dell Marie Hamilton’s work, “The End of Susan, The End of Everything,” is also on display.

Hamilton, born in New York, often explores themes relating to gender, history, and memory through the human body in her work, which are also seen in her ICA installation.

Hamilton created the installation to couple her own artistic creations with the various possessions of Susan Denker, a mentor and friend who passed away suddenly in 2016. After Denker, who was also a faculty member at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, passed, Hamilton inherited many of Denker’s belongings.

Hamilton’s work is separated into three sections that are modeled after the living room, study, and bedroom of Denker’s apartment in Cambridge. When one enters the room, they are blanketed by an inviting, warm feeling that emulates Denker’s home.

“It’s not what you’d traditionally see in a museum,” Scullin said.

According to the ICA’s didactic text, Hamilton uses her own body, as well as Denker’s possessions, as a vehicle to attempt to answer the question, “How do we make meaning out of what is left behind after someone dies?”

An ICA visitor assistant who declined to provide their name to The Beacon said Hamilton’s work is “like a memorial, but less dark.”

Viewers experience the feeling of Denker’s life being memorialized, but in such a way that evokes more joy than sadness.

On one wall of the room spans a long, white bookshelf with multiple cubby-like spaces filled with books, magazines, and DVDs. Literary works and images of famous Black leaders, including Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and former president Barack Obama, stand out in the front of the shelves.

On the next wall sits Denker’s desk below another shelf spanning the wall. Above her desk plays a video called “Jackson Pollock: Two Figurative Alternatives,” in which Hamilton takes on the role of Denker in a performative reading, as well as the role of Pollock when painting in his splashed paint style.

Hamilton’s presence in the video, surrounded by Denker’s possessions, gives the impression of a loving, mother-daughter-like relationship between the two.

On the third and final wall, there are two smaller bookshelves decorated with records, books, and family photos. Also displayed on the shelves are some of Denker’s everyday items, such as a camera, a pair of glasses, seashells, and a restaurant menu.

Hamilton included some of her own objects, intertwining Denker’s life with her own, but one cannot tell which objects belong to whom, developing an understanding of the intersectionality of their personas. The intent of doing so was to display Denker’s life through a selection of objects.

“I think about that and my belongings and how someone would choose to represent me,” Scullin said.

Like Scullin, viewers are encouraged to question the relationship between life and death through Hamilton’s work, pondering how the dead have the possibility of being “resurrected” through the relationships they form with others.

The “Raúl de Nieves: The Treasure House of Memory” exhibit, by Raúl de Nieves––a New York based artist, musician, and performer––consists of seven lavish sculptures. Five free-standing sculptures are made of fiberglass, metal, beads, and other hardware. Two sculptures hanging on the wall make use of everyday objects, such as postcards, fake flowers, and plastic toys.

“[Raúl’s work] also creates this extra dialogue of exploring your own way of creating with these mediums,” ICA visitor assistant Jannella Mele said.

de Nieves’ sculptures explore the transformational abilities of identity. His work references costumes from traditional Mexican culture and relates to religious iconography, mythology, and folktales. He also integrates drag, ballroom, and queer club culture modes of fashion into his art.

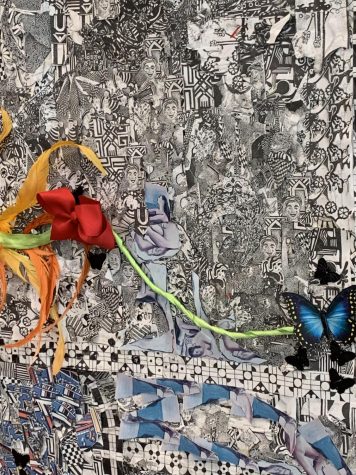

One of the sculptures in “Raúl de Nieves: The Treasure House of Memory” exhibit.

The narrative of de Nieves’ work evokes feelings of unity, and the interconnection between the sculptures is undoubtedly breathtaking.

“In this beautiful exhibition, all the pieces are interconnected,” said Yuzhu Wang, another visitor assistant. “The curator and the artists did a great job.”

The story told throughout de Nieves’ exhibit starts with a free-standing, three-panel painting in the style of a room divider, titled “The Battle of Saint George and the Dragon,” referencing a legend told throughout Byzantine culture about Saint George and a dragon. Swirling outlines of faces paired with a multitude of colors allow one to feel connected to the art.

Dispersed throughout the room are three sculptures. de Nieves uses bright-colored beads and fiberglass to sculpt the curved and misshaped human figures, appearing to be morphing into a horse.

One of the sculptures in “Raúl de Nieves: The Treasure House of Memory” exhibit.

The bending shape of these sculptures creates a sense of movement, building on de Nieves’ central theme of transformation, but also a sense of discomfort, successfully portraying de Nieves’ themes relating to intersectionality and identity.

“Raúl is really a master of the body,” Mele, the visitor assistant, said.

In the center of the room stands a life-size sculpture of a horse on its hind legs. The horse’s pose gives off an initial sense of dominance. However, upon a closer look, feelings of joy and love are provoked by de Nieves’ hidden messages.

“A lot of people interpret it as defensive but I don’t really see it that way.” Said Wang as he pointed out a small key embedded in the horse’s body that reads, “Whoever holds the key can unlock my heart.”

On a side wall sits a large map consisting of colorful ribbons, feathers, yarn, and glitter layered on top of de Nieves’ black and white drawings and vintage postcard reproductions.

One of the sculptures in “Raúl de Nieves: The Treasure House of Memory” exhibit.

Hanging on the back wall sits the large circular collage, “The Leap into the Sun.” This piece gives off a portal-like effect that entrances the audience with an array of emerging colors and materials.

de Nieves’ themes of personal transformation are seen throughout each piece, as he layers colors, patterns, and shapes to create pieces that ultimately evoke joy.

The works of Forrester, Haines, Hamilton and de Nieves each use a contemporary and unique artistic style, providing one with the opportunity to question the artworks’ meaning and look beyond its surface for deeper cultural interpretation and importance.

With the artists’ exploration of themes relating to personal culture, identity, power and interconnection of present-day societal issues, a distinctive artistic narrative is created for one to explore.