There was no disco, yet the ball kept spinning above us, and as much as I wanted this moment to freeze forever it would not—still, I could not help but overflow; because music this beautiful could not be clung to like water, only felt—and if not for my eyelid’s border or the skin of my eardrums, I would have melted all together.

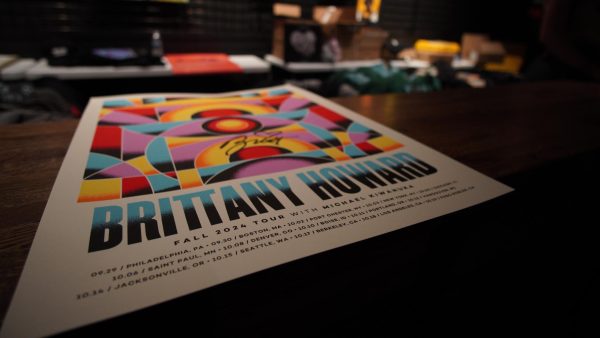

Michael Kiwanuka shared the Boston leg of his co-headline tour with Alabama Shakes’ Brittany Howard last Monday, performing songs from his eponymous Mercury Prize-winning collection “KIWANUKA” in anticipation of his fourth full-length album “Small Changes,” set to release on Nov. 15.

Hearts broke and heads bowed. I listened. I have been listening since 2016’s “Cold Little Heart,” a 10-minute epic best described in three movements—the prelude of which, begins with a rather unassuming slide guitar motif that builds into the main section where Kiwanuka’s conflicted lyrics about when to walk away from love and when to keep trying lead the song into a brief outro: the bridges he crossed, the questions he asked, all stripped back, guided by just his voice and guitar, laid bare, before the opening theme returns—which is at its very best live. As his mouth opened, his eyes closed. So did mine.

Vision—in a place like this; an idle compromise, sacrificed for salvation. Moot.

Over Pink Floyd–adjacent textures and R&B-chic orchestration, Kiwanuka sang about everything between diaspora and distance, gripping neo-soul by the neck of his electric guitar strings like a steering wheel, with a smoother-than-raspy voice that Marvin Gaye’s British bluesier cousin would have had. He did seem lonely that night. Despite the backup singers to his right and being surrounded by a full band, he tried to maintain eye contact with all of us through his eyelids’ closed curtains—he tried to reach us.

Kiwanuka’s latest single, “Floating Parade,” released last month with a music video by American filmmaker Philip Youmans: it follows glitter-clad silhouettes of extraterrestrials with bleached eyebrows venturing past the wilderness they landed in, peeking past cracks of suburban picket fences at how the other half lives, in their white-washed worlds of art, their language of pretense, and among them, a dancer surrounded by bodies—his own, reaching out to grasp that ivory kingdom through the visor of a pink cotton candy funnel as he twirls against the sky behind him, the rolled-up backdrop like a broken window—a bumper sticker of the place he came from, a place remembered in two dimensions.

He closed out the show with “Love and Hate,” a ripping guitar solo by his guitarist Michael Jablonka, and a memo of his heartbeat, the song’s refrain:

Ba-ba-badum-bum budum budum / ba-ba-badum-bum badum budum

The song is the title track off his 2016 album of the same name; about those lonesome moments on stage when it feels like everyone loves him—not that he’s the only one there, but because this experience is exclusively Kiwanuka’s. He knows he must return to life beyond the stage. His voice is a way out of doubts and demons, for our occasions on the highway between home and heaven—to us, permanent, pocketed, streamed. So once the button gets pushed, he looks to the audience for answers—after the music, when the lights go out and the show can’t go on, if they can accept him or not.

“People coming to shows and listening to music is what keeps the world alive,” said Kiwanuka.