When Associate Professor Marc Fields finished his documentary “Give Me the Banjo” after a decade of researching and gathering content on the instrument’s history, he knew he hadn’t told the full story yet.

In Fields’ earlier work, he completed several projects about early American culture and entertainment and repeatedly saw the same trend: the banjo.

After the release of the PBS documentary in November 2011, Fields and Assistant Professor Shaun Clarke, the project manager, developed a website through Emerson allowing Fields and Clarke to present the banjo’s complete history by including content they weren’t able to initially include.

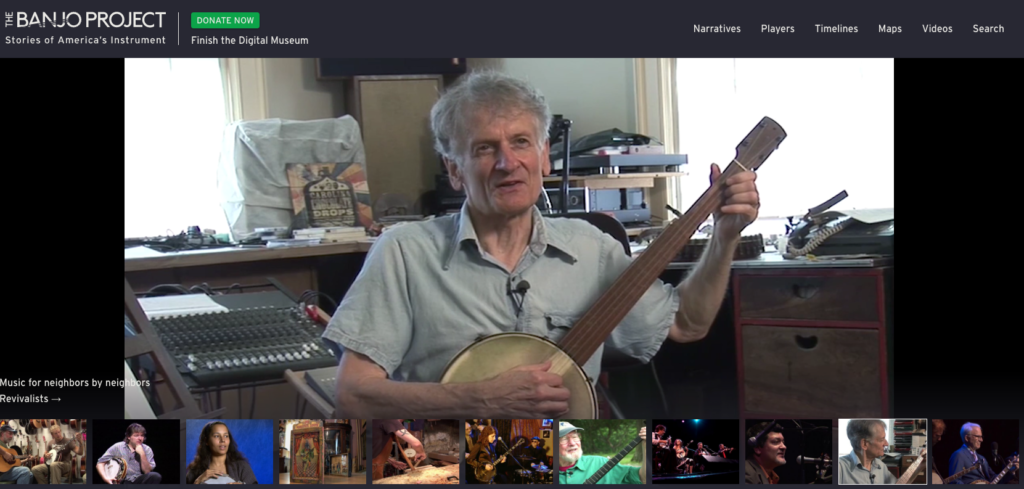

The digital museum, named The Banjo Project, comprises over 300 hours of banjo-related content and is now online in a beta version. The project will be completed in June 2019, according to Fields.

“I knew pretty soon after getting into it that a one-off feature documentary, even if it was 90 minutes long, wasn’t going to adequately cover the full history and all its complexities,” Fields said.

Viewers can find live performances, narratives, timelines of historical context, maps, and key events in the digital museum. The museum also showcases interviews with banjo players, makers, and scholars.

“The online platform allows people to follow the aspects that interest them the most, but it always connects them with additional material and information if they want to pursue it,” Fields said. “It appeals to potentially a much broader audience that ranges from people who know next to nothing about the banjo, but there’s something that piqued their curiosity—whether it’s a song or a performer—to people who are the real banjo geeks.”

Before he began shooting his documentary in 2002, Fields said he realized there was a story to be told after listening to Tony Trischka’s 1993 album World Turning, which includes performances in different historical styles—from West African to punk—all played on the banjo.

“That was a eureka moment where I realized that I could actually tell the history of America’s popular entertainment or popular music through the evolution of the banjo,” he said.

The digital museum completed the documentary’s work by capturing the banjo’s evolution, from its entrance into the United States by enslaved Africans, until today, according to Fields.

“I think we have a difficult relationship with our past as a culture because so much of it is the result of very serious kinds of prejudices and misunderstandings,” Fields said. “The banjo as an icon—so to speak—has gone through a lot of different stages that all tend to whitewash the contested aspects of it.”

Fields said the banjo underwent several changes from African and European Americans, and it shaped most American musical styles starting from the minstrel show—an early nineteenth century form of entertainment where white people caricatured plantation slaves—to jazz, folk, blues, country, and more.

Though the banjo is one of America’s oldest instruments, it still remains what Fields referred to as a “snubbed” instrument, often carrying stereotypes that even Clarke said he believed prior to working with Fields.

“When I started working with [Fields], I had limited knowledge about the banjo. A lot of what I knew was through the stereotypes that a lot of people have about the banjo in our contemporary society,” Clarke said.

Many still associate the banjo with white, rural people living in the Appalachian Mountains, according to Fields. He said he thinks these misconstrued opinions about the instrument didn’t help the idea that it was a respectable, or even an intelligent, part of American culture.

“We listen to so much music that’s influenced by the banjo, and we don’t even know it and so it’s important for people to understand the history,” Clarke said.

Ethnomusicologist and Author Kip Lornell gave interviews for the Banjo Project a decade ago, and his videos are now featured on the digital museum. In his interviews, he explained the transformations the instrument underwent and the origins of these stereotypes.

“It’s those three things: the passage of time and history, a change in racial identity and then in identification, and the third is the commodification and the commercialization of the banjo,” Lornell said. “All those things helped to transform an instrument that was clearly of African origin to one that we now associate with white America, and usually with the South as well.”

Lornell emphasized that the banjo is a versatile and interesting instrument and that a project like the digital museum could help break these stereotypes.

“The Banjo Project online is a very good thing, because eventually some people will find it and they’ll listen to old-time banjo players like Charlie Poole and they’ll listen to Béla Fleck and say, ‘This is some good stuff here—maybe I should listen to a broader range than I’m listening to’,” he said.

Fields said The Banjo Project, like other museums, will never be finished, and they will try to keep it updated with new content.

“One of my reasons for doing this is just to open people’s eyes and ears to the incredible range of music that the banjo has been associated with,” Fields said. “Not just to think of it as an artifact of another area but something which has cultural significance, but also is a tool for great musical expression.”