Dozens of Emerson students gathered in the 2 Boylston Place alleyway on Friday afternoon to protest the upcoming 2 percent tuition increase.

In response to a rise in tuition and room and board charges for the upcoming academic year, announced by the college on March 17, Emersonians organized the tuition protest through a social media campaign. The account @stopraisingtuition urged attendees to wear black and bring posters and sign an online petition to the administration.

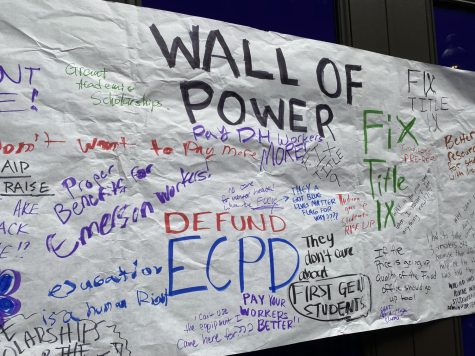

The protesters’ petition lists five demands, including fiscal transparency through an annual financial town hall, improved financial aid resources, and increased student involvement in financial decisions.

Beginning at 4 p.m., a crowd of over 50 people flocked to the alley for the hour-long event. To kick off the event, organizers passed around a black megaphone and shared their thoughts on the tuition increase.

“When is it going to be enough?” shouted one organizer, sophomore theater and performance major Joe Nalieth. “For the administration, it’s never going to be enough.”

Organizer Neiko Pittman said the college’s move to increase tuition must be balanced with increased financial aid and access to resources.

“So much of our money is allocated to recruiting new students and talking about the programs we have rather than making the programs we have more accessible and available,” the sophomore visual and media arts major said.

Nalieth also asked protesters if their education had increased in value in accordance with the tuition hike—which drew a chorus of “no”s. He then shared what he believes are Emerson’s unnecessary expenses.

“Let me talk to you for a second about [the Emerson College Police Department],” Nalieth said. “Why do they get millions of dollars every year? Just to park their car out front and intimidate students?”

He also pointed out that students with on-campus jobs make Massachusetts minimum wage—$14.25 per hour—rather than the $15 that has been pushed nationwide.

“Come on Emerson, pay your students!” Nalieth said.

The acting major said that the time was ripe to reimagine students’ roles in college financial decisions. He touched on the nearly $1 million salary paid to Emerson’s last president, Lee Pelton, and the absence of a current permanent president, to emphasize the opportunity to restructure the relationship between students and administrators.

“We are in a moment as a university that is the perfect opportunity to give students increased agency in the decision-making process—we don’t have a president,” Nalieth said. “What do we have in the meantime? An interim president they dragged out of retirement? What is he going to do for us?”

Nalieth mentioned examples from the Emerson community that provide insight into how to challenge the college.

“Emerson College doesn’t like that the faculty has a union, they don’t like that the staff organize and fight for their wages and fight for their treatment,” Nalieth said. “Maybe we should do something like that! Maybe we should start thinking about long-term solutions to this problem!”

Beyond the single issue of tuition hikes, the crowd also aired other grievances with the college.

Sophomore visual and media arts major Nyasia Mayes, another protest organizer, called attention to the college’s misrepresentation of its own diversity.

“How many Instagram posts…we see someone of color happen to be there?” Mayes asked the crowd. “It’s important that [Emerson] also realize the racial inequities that they inhabit.”

Emerson is a predominantly-white institution, according to the college’s 2021-22 factbook.

First-year political communications major Annie Douma took the stand to argue that the college should treat students and faculty equitably. She noted that one of her professors had to step away from teaching this semester because of safety concerns for her immunocompromised mother. Instead of accommodating the professor by moving the class to a virtual option, a different professor was brought in to teach.

“That shift was not something I signed up for, and it was directly a result of the college not being accommodating to the fact that COVID is still happening,” Douma said to The Beacon.

One student told the crowd that they wouldn’t have been able to attend Emerson if they hadn’t been selected as a resident assistant, and therefore exempted from paying room and board, and if they didn’t have access to scholarships and jobs.

“I am incredibly lucky to be in this position,” they said. ”Where is this [assistance] for everyone else too?”

Nalieth claimed that international students are rarely given financial aid offers, drawing a cry from an international student in the crowd: “If you want to keep us around, give us our money!”

A first-generation student also took up the bullhorn and stated that when they emailed the college about financial aid, they didn’t get a response for two weeks before ultimately being denied an offer.

“If they continue to raise tuition, I will not be able to continue to go here,” they said. “First-generation students will not be represented. That is what Emerson is representing.”

Friday’s demonstration was not the first organized by this student-led coalition, which was originally created to make a stand against the administration’s previous tuition raise for the 2021-22 academic year. Those demands were not addressed by the college.

Last year, the group met with administration members and trustees but said they encountered resistance.

“They were largely not receptive,” Nalieth said to The Beacon. “It felt patronizing or condescending. They seemed to think that we were the only people who cared. So when we saw the email [announcing the raise] this year, we knew that we had to mobilize immediately and get people outside and prove to the administration that this is not an isolated concern.”

The group hopes to get more students involved in their campaign so the administration will respond to the demands.

“We’re planning more events in the future,” Mayes said to The Beacon. “It’s about tuition, but it’s also about coming together because when we come together. That’s how a change is made.”

The administration’s lack of response to the concerns was not because of its justification of tuition increases, according to Nalieth.

“It actually was a lot more pathetic than that,” he said. “It felt like they were throwing their hands up.”

According to Nalieth, college administrators had told them that the board of trustees was responsible for tuition matters and financial aid allocation, while the trustees the students met with explained that they couldn’t tap into the endowment at their own discretion because funds are reserved for specific purposes.

The organizers describe themselves as a decentralized organization autonomous from the school, meaning they want to create a student power structure on their own. Unlike previous movements, the group is not advocating for a tuition strike, citing the potential for disproportionate harm—especially to marginalized students.

“I personally acknowledge that if administration doesn’t listen to these demands, we’ll be left with no other avenue,” Nalieth said. “We have to hit them where it hurts in the funding.”

College spokesperson Michelle Gaseau said Emerson is willing to listen to the issues students raised at the protest.

“The College is open to dialogue and conversation with students about their concerns and is committed to working with our students, amidst the competing demands on the College, including infrastructure needs and a rise in inflation, to ensure they are able to continue on the path to graduation,” Gaseau wrote in an email statement to the Beacon.

The protest organizers encourage students to apply to the tuition offset fund, but the ultimate goal is to achieve more substantial gains for all.

“Emerson College needs to address this problem beyond trying to slap band-aids on top of the systemic problems that they’re creating,” Nalieth said.