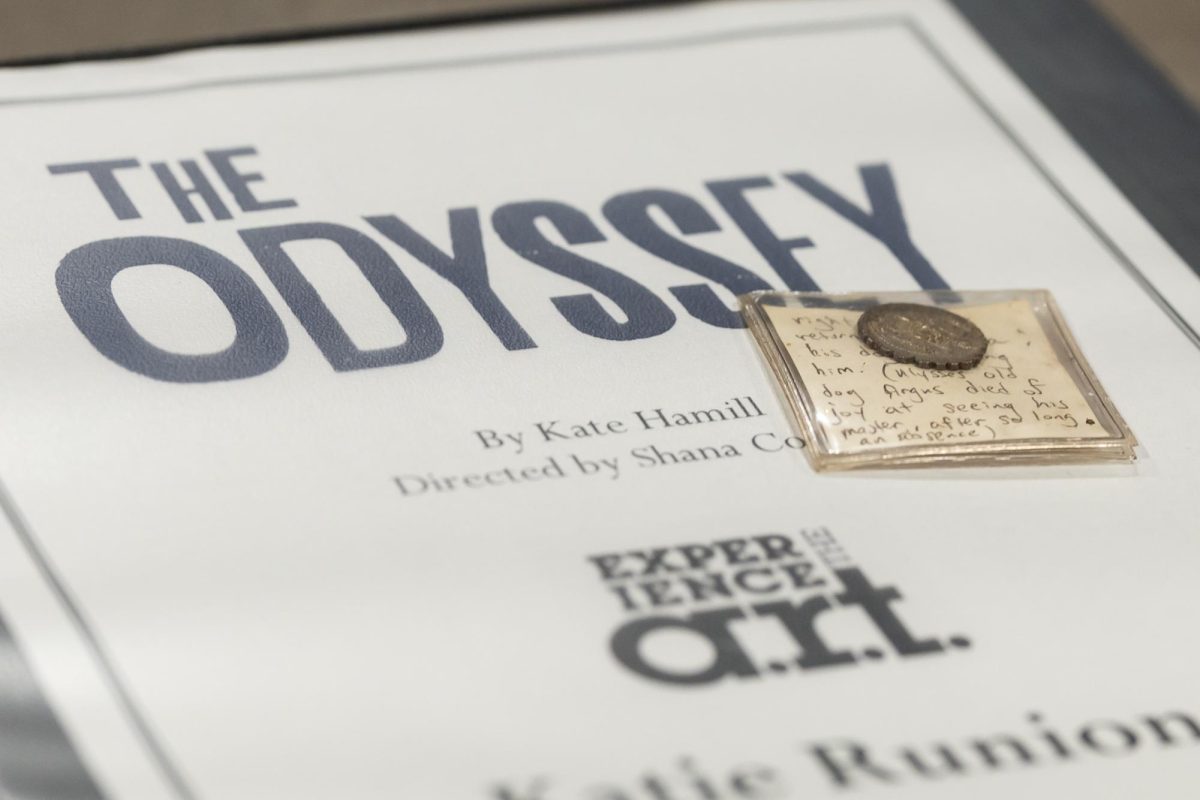

Actor and Playwright Kate HamillŌĆÖs latest production, ŌĆ£The Odyssey,ŌĆØ will have its world premiere on Feb. 9 at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge. Directed by Shana Cooper, the three-act play adapts HomerŌĆÖs ancient Greek epic into a war story for the 21st century, told from both combatant and civilian perspectives.┬Ā

HomerŌĆÖs version begins with the king of Ithaca, Odysseus, estranged after fighting in Troy for the last decade. His commute back home proves more daunting than the brutal war: the trip itself takes 10 more years, spanning his encounters with tentacled sea beasts and a man-eating cyclops who also sheperds, the latter of which culminating into a nasty grudge with the giantŌĆÖs daddy, vengeful sea god Poseidon, leaving Odysseus shipwrecked on numerous remote islands. Meanwhile, his faithful wife Penelope waits for him with their now-adult son Telemachus back home, weaving a tapestry of him as waves of desperate suitors try to steal his vacant throne.┬Ā

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs a play without villainsŌĆöa lot of people who perpetuate violence are also haunted by it,ŌĆØ said Hamill. ŌĆ£This play has taught me a lot of compassion for people who do inexcusable things because they felt like they had to.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Cooper found HomerŌĆÖs version too and male-centric to be relatable. HamillŌĆÖs rendition embraces resilience and forgiveness, narrated by three women who were real survivors at Troy. Odysseus is not the hero. And Penelope doesnŌĆÖt just spend 20 years crocheting out of grief, like in the original. SheŌĆÖs allowed to move on. She thought her husband died. But he survived an active war zone for 10 years just to do it all over again, this time on a boat, as the Mediterranean does its darndest to kill him.┬Ā

In war, everybody hurts.┬Ā

Trauma is a difficult emotion to nail down, much less overcome. Hamill was influenced by Ken BurnsŌĆÖ Vietnam War documentary, ŌĆ£The Vietnam War,ŌĆØ but her and Cooper owe much of the playŌĆÖs authenticity to friend and fellow actor, Stephan Wolfert, whose feedback was ŌĆ£invaluable,ŌĆØ according to Hamill.┬Ā

Wolfert, who formerly served in active duty, has since become a licensed therapist specializing in trauma practice, helping other veterans process their service through theater, mostly Shakespeare. He was a consultant on ŌĆ£The OdysseyŌĆØ through its seven-year-long development: during writing, at workshops, and in one-on-one meetings with the cast.

Cooper says her directing style is partly influenced by the Ashland Shakespeare festival in her hometown where, as a child, she would watch plays for hours. At the time, she didnŌĆÖt know what the words meant, but she could still follow the stories emotionally.┬Ā

For example, the play is set on a ship, so production design needs to express what it feels like to be surrounded by sea, hopelessly strandedŌĆöbut that doesnŌĆÖt mean theyŌĆÖre building a Titanic replica and flooding the theater. ItŌĆÖs about activating the audience with visual cues, poetically.┬Ā

ŌĆ£I ask designers how we can create little invitations for the audience to then complete the images with their own imagination,ŌĆØ said Cooper. ŌĆ£This idea of telling epic large-scale stories has been with me since childhood.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Still, the play has its punchlinesŌĆöbetween those brutally honest scenes meant to depict the veteran experienceŌĆöthere are definitely theatrics too, like shadow puppets, vibrant choreography, and men who turn into bipedal sheep.┬Ā

ŌĆ£My son was two-and-a-half when we started, and now heŌĆÖs ten, about the same age as Telemachus,ŌĆØ said Cooper. ŌĆ£There was so much life that happened as we were working on this playŌĆöpandemic, huge wars.ŌĆØ

Hamill herself plays Circe, a notable nihilist in her version of the Odyssey, a stranded witch gone bad because the world rejected her. At first, she might seem like archetypal feminist queen, but later audiences find out sheŌĆÖs just as toxic as the men sheŌĆÖs making swine of.┬Ā┬Ā

ŌĆ£I came up with the idea to write the play at a protest in 2016 during TrumpŌĆÖs first election,ŌĆØ said Hamill. ŌĆ£At the time, it felt like the end of a civilization, but IŌĆÖve learned that people survive.ŌĆØ