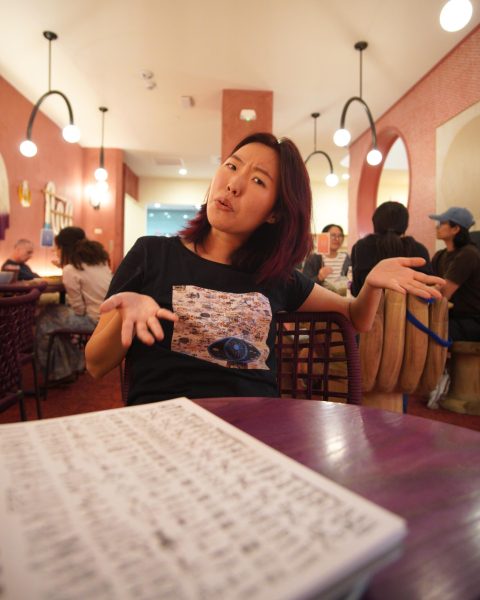

Becky Moon told me to imagine a tomato‚Äîand in my mind, one appeared: minimal gloss, blush red, fresh and bulbous with a fuzzy green toupee and barcode sticker. I know the taste‚Äîeven what its insides look like, what a tomato feels like‚Äîand yet, there was no tomato before me, my mouth was empty, my hands cupping nothing, and if she were to split my head open then, we would find the pea-sized niche of my skull equally tomatoless. If I can think of one, then there exists a tomato within me, that much is certain‚Äîbut where is it?¬Ý

‚ÄúI like to draw the tomato in my head,‚Äù said Moon.¬Ý

Moon had a brief six-week excursion in the Connecticut countryside at Yale Norfolk Summer School of Art, back when she was one of 26 rising seniors from around the world working out of a middle-of-nowhere “art barn”—she was chased by a skunk and they all saw bears, it was the summer before we all went brat. She recalls being split into two groups, each given a ball of yarn tied to a pole and then instructed to walk the yarn back together into a ball once they unraveled it; and, in the process, made art with what came loose.

‚ÄúThe other group did this cool hip yarn installation in the cafeteria but our group played dodgeball with it,‚Äù said Moon.¬Ý

CAMBRIDGE—Moon began working part-time at the MIT Museum and illustrating weekly for the Ig Nobel Prize Blog by the Annals of Improbable Research magazine back in August, a bimonthly science publication combining academic satire with science-meets-indie—after meeting editor and master of ceremonies, Marc Abrahams, on a chance encounter in the neighborhood while he was walking his dog, Wednesday, who dropped anchor, and Moon, who happened to be there too, took a photo. She grew up in South Korea, a country with five Ig Nobel winners, and has been a fan since childhood.

“The Awards make everyone aware that there is always research that makes you laugh then think. So many discoveries never really leave the lab, but with the Igs, we get to pay attention to them,” said Moon

I met Moon at the Murphy’s Law-themed 34th annual Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony at MIT last month—and in response to Murphy’s eponym, that is to say, “everything that can go wrong will go wrong,” she wore a toast costume with jam spread on one side because, in the event of a fall, “the jam side always lands first.”

She seemed like someone who‚Äôd never dropped anything before‚Äîthough always one to turn over those who had already fallen; making them face the other way, upwards and towards that endless ceiling, in case there was ever anything there that they missed looking at‚Äîwhich is what it feels like to experience her art.¬Ý

The gala was followed by a reception at the MIT Museum featuring a Q&A, where Moon, the panel‚Äôs timekeeper, wore a banana suit as per tradition‚Äîso when speakers had one minute left, she would walk up ever so slowly, politely menacing them into sitting back down.¬Ý

“One banana is a little misdefined, but three bananas is both goofy and intimidating at the same time, so I bought three banana suits,” said Abrahams.

She spent a few days in Ithaca, NY with philosopher and major influence, Susanna Siegel, after they collaborated on “Sea Of Perception,” a joint exhibit in Harvard’s Philosophy Department last October with paintings by Moon and inspired by Susanna’s research of phenomenology, or lived experience. Moon reached out after reading Siegel’s “Vigilantism and Political Vision” in the Washington University Review of Philosophy’s second volume, which she drew the covers for back when she studied there.

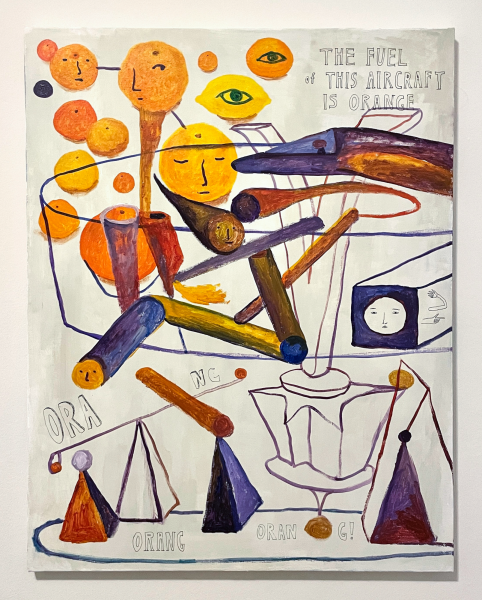

“The history of Western philosophy tends to dismiss the idea that rhetoric and images can play any central role in philosophical thought. But [Becky] was just like ‘I can paint ideas’—and she can—there are philosophy lessons in Becky’s paintings,” said Siegel.

Philosophical research is not about answering questions; there are only possibilities to consider and consequences to respond to—which, in turn, lead to more questions. In the process, philosophers are understanding the problem via essays, papers, novels, films, and in Moon’s case, art—hers especially, accessible and tangible, anything but self-selective, the very antithesis of an ivory tower.

Moon‚Äôs inner world is witty, full of intersections between philosophy and her own lived experience‚Äîdepicting phenomenology by inviting viewers to perceive it for themselves.¬Ý

“There’s this whole stigma [about philosophy] that’s just guys with beards sitting in armchairs, they’re not,” said Moon.

For example, ‚ÄúWoodlover‚Äôs Affordances,‚Äù embodies, well, affordances‚Äîi.e., the way chairs afford sitting, cups afford drinking, shirts afford wearing, etc. Here, wood transforms these expectations, embracing all of them at once, even finding kinship among snails, comparing their spiraled shells to the age rings of a split trunk like Saturn‚Äôs collar, dynamic despite being cleaved into pieces‚Äîall the things one can do with wood, mostly those we‚Äôd never think of.¬Ý

Moon’s first impression of modern philosophy was in seventh grade after acting in an adaptation of Franz Kafka‚Äôs ‚ÄúThe Trial,” where she played the assistant.

‚ÄúIt was an absurdist play and I remember making 200 paper airplanes. I lay on the floor and just threw them as I said my only line; ‚ÄòMr. K, you have a phone call,‚Äô‚Äù said Moon, in reference to Joseph K., the novel‚Äôs main character.¬Ý