The journalism major at Emerson College has become an attractive destination for media-inclined undergrads as it consistently ranks highly among college list publications like Prep Scholar and College Factual, where it places 9th and 12th, respectively, as of 2024. In the 27 years the Emerson Journalism Department has existed, its success has been well documented through metrics such as these.

“One big reason Emerson still ranks in those polls lies in how long it’s had a journalism department and how long that department has been highly regarded,” Tim Riley, an associate professor in Emerson’s journalism department, said in an interview with the Beacon. “We were the first to turn a broadcast track into a major, and have always led the field in our commitment to … technological innovation … [and yet we still] balance practitioners with academics.”

What is less well documented, however, is how the major and the Department of Journalism at Emerson developed to become as specialized, diverse, and innovative as the faculty says it is today. How is it that what started as a school of oratory would become a nationally recognized leader in journalism studies and a pioneer in multimedia reporting? At first glance, the answer appears to be opaque.

The landing page for Emerson’s website on its history and preservation devotes only one line to journalism, stating that Emerson “created the first course of journalism in the 1920s.”

The latest internal document on the history of the journalism department was written two years ago by Associate Professor Paul Niwa. Niwa said every department on campus updates its history every five years.

However, even this document, which was approved by both department faculty and Emerson Academic Affairs, states, “The College archivist has no information on when the first journalism course was offered at Emerson College.”

Given this information, the inception of the journalism major at Emerson might have been forever lost to time. Or it would be, if it weren’t for the time-worn Emerson College Bulletin Catalog Issues found at the College Archives on the second floor of the Walker Building. These books documented the course offerings, housing information, and student and faculty members of the college for each academic year dating back to the 1920-21 school year.

The 1920s are notable for being the decade when the college expanded its course offering from strictly oratory studies, which paved the way for more diverse fields of study to emerge. It is here, in the 1927-28 academic year, that the first journalism course was offered. This was a time when tuition was $125 per semester to attend the still named “Emerson College of Oratory,” when on-campus dormitories were reserved for women only, and when the campus was located at 30 Huntington Avenue near Copley Square, across from the Public Library (in what today is smack dab in the middle of a westbound entrance to Interstate 90 according to Google Maps).

Emerson boasted three publications at the time, “The Emerson Quarterly,” “The Alumni Bulletin,” and “The Emerson College News,” but none were specifically operated by the students and were distributed mainly to alumni.

Simply called “Journalism,” this initial course offering was a first-year course and the 18th and newest course in the English field of study.

The course description read: “Lecture course in news and feature writing for modern newspapers, combined with practical training through the Emerson Press Club, whose members are assigned as actual correspondents for the College on various Boston and out-of-town papers. Special lectures from time to time by well-known writers of news and fiction.”

The course “Journalism” would continue to be offered until the start of the ‘40s with the same description, though in the 1929-30 academic year, it would be offered under the study field “Language and Literature.”

Important to understanding the course offerings of this time is that Emerson’s curriculum used to be much smaller and more centralized to oratory studies. From 1920-29, there were not multiple schools but one curriculum of roughly 80 courses divided into seven study fields: Oratory, Voice Training, Literary Interpretation, Dramatic and Platform Art, Physical Training, Language and Literature, and Pedagogy.

In the 1933-34 academic year, “Journalism” was re-subsumed under English when the study field of Language and Literature changed to Literary Interpretation. Both these study fields were offered alongside Drama, History and Social Science, Physical Training, and Education and Psychology.

The ‘30s continued to see developments in the character of the college away from oratory and toward communication and the arts. 1937 saw the college award the first Bachelor of Arts degree, and by 1939, “of Oratory” was dropped from the name in favor of simply “Emerson College.”

By the end of the 1930s, when tuition per semester cost $180, journalism remained a one-course offering under the English department. At the same time, radio and broadcasting had expanded into their own field of study under the “Speech” discipline.

The next milestone in the development of journalism at Emerson came in the 1941-42 academic year with the inclusion of “Elementary Journalism,” “Advanced Journalism,” and “Feature Writing” courses in place of the previous course.

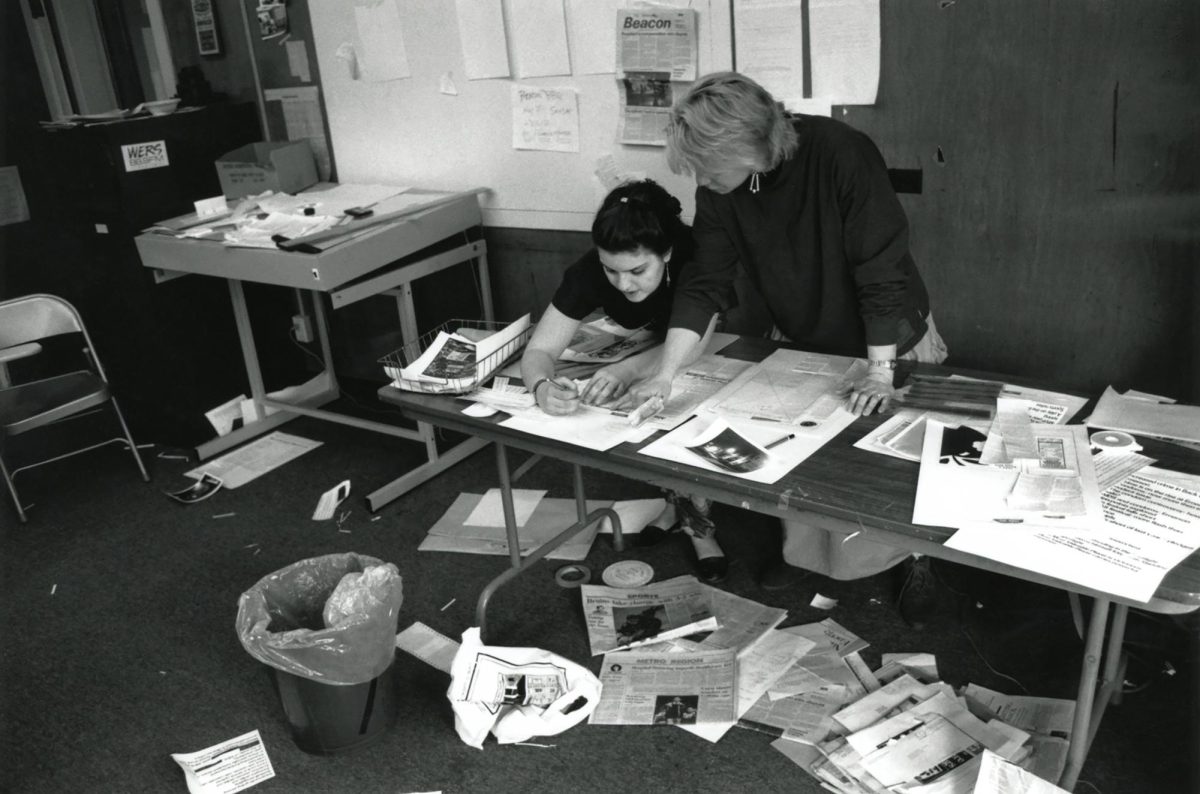

This decade would also see the development of the first campus news publication run entirely by student journalists, Emerson’s own Berkeley Beacon, in 1947.

The Beacon got off the ground thanks to funding from the newly formed Student Activities Fund, which was created by Boylston Green (no relation to Boylston St., no relation to Green Line), Emerson’s fifth President during his first semester at the helm in 1946, according to the book, “A Century of Eloquence: The History of Emerson College, 1880-1980.”

The most notable act of the Student Activities Fund was the creation of a tuition-included “activities fee,” which was a built-in way to ensure funding for student organizations. The fee in 1947 was $7.50 per student per semester and was divided into $3 for class dues, $2 to the Emersonian student yearbook, $1.50 to the Berkeley Beacon, and $1 as dues to the Student Government Association (SGA). The student activities fee remains part of Emerson’s tuition to this day, still overseen by the SGA, and in 2023, it was evaluated at $472 per student per semester.

Also in 1947, Emerson’s first college radio station, WECB, would be established. However, at the time, it was used to host mainly entertainment such as play readings rather than news and could only be broadcast through the college wires rather than over the air. In 1949, this problem was remedied by the creation of WERS, a public FM radio station that could go out over the air. WERS would receive an FCC operating license in the fall of 1949, thanks to professor Charles Dudley, who, after coming to Emerson in 1946, would largely revolutionize its broadcasting offerings.

In the following decades, broadcasting was the most rapidly expanding field of interest at Emerson. Broadcasting became its own department long before journalism ever did, due in part to the work of Dudley, who would go on to teach dozens of classes in broadcasting, including a single course offering of broadcast news, before his resignation in the late 1960s. Disenfranchised by the rise of commercialism in the television and radio industries, Dudley stepped down, saying that the future of broadcasting was “all downhill as far as I’m concerned,” according to the historical book on the college

The Broadcasting major itself had become crystalized under the tenure of Samuel Justus McKinley, Emerson’s sixth president (1952–1967). Before this, many of the major course offerings had equivalents in the Radio Speech study field of the mid-40s.

Most of the information from the 1970s to the present comes from the internal history of the department. It states that according to Professor Emerita Marsha Della-Giustina, who arrived at Emerson in 1977, around 100 students were enrolled in print journalism studies at that time. According to the document, “Dr. Della-Giustina was hired to build the broadcast journalism component of the program.”

“We used to have a broadcast track and a print track, and we’ve done away with those,” Riley said.

He has been teaching at Emerson since 2009. In the modern curriculum, he said, “print is just really merged completely with the web and social media and multimedia.”

In the 1990s, the college underwent re-organization, creating the School of Communication and the Journalism department in the 1997-98 academic year. It was called the Department of Journalism and Public Information then, though it would be changed shortly after. The department replaced The Division of Mass Communication, which was the closest precursor to a journalism department that taught broadcast journalism for decades before this.

The mission statement of the department in its current iteration, as quoted in the internal document, is “to be at the forefront of the digital evolution and revolution,” and cites Emerson as being “one of the first programs nationally to break down the traditional silos of print and broadcast and offer a dedicated multimedia curriculum.”

Riley has been teaching multimedia through JR 103, known currently as Multimedia Journalism, but formally The Digital Journalist. Before that, Emerson’s multimedia course offering was a more lecture-focused class called Images and Media, which Riley also taught after he arrived in the late 2000s. He said multimedia went from an emerging discipline in journalism that Emerson was at the forefront of, to quickly becoming the industry standard as journalism overall changed.

“When I started … everyone was emphasizing how multimedia everything is,” Riley said. “Now nobody even talks about it. It just is all multimedia all the time.”

Riley sees the future of journalism at Emerson taking on even more of a focus on social media.

“The shift in the Twitter situation is something I watched pretty carefully,” Riley said. “The fallout from that is Substack is growing immensely, and very quickly, it’s turning into a real important space for journalists.”

Data analysis, Riley said, will also become an important part of what Emerson’s future journalists will need to know going forward. He said the implementation of data visualization software like Dataviz into the curriculum is a way that Emerson continues to be cutting-edge in its pedagogy.

“We’re sort of drowning in all these different oceans of data, but tapping that data and using it to tell stories is turning into a real fine art of a journalism skill,” Riley said. “We have hired faculty specifically devoted to data journalism … that’s an area that we think is really important for the future … because more data is becoming available.”

On faculty, Emerson has built its journalism department on not just full-term faculty but also term faculty, or journalists-in-residence, “all of whom have extensive and prominent journalistic experience that enhances their classroom work,” according to internal department documents. Emerson’s journalism department now has four journalists in residence, two of whom are designated as senior journalists in residence.

As a part of the focus on emerging and multimedia journalism, the department moved in 2003 to the Walker Building. This followed the college’s overall transition from Back Bay to the Theater District, where construction began on the 6th-floor Walker newsroom and labs to help build up what the department called “a convergence curriculum.”

Another noticeable change in the past 15 years is that the diversity of the journalism faculty has “transformed,” according to Riley. Riley said that faculty numbers in the college and the department have increased, with a 40 percent growth in overall faculty since 2009, but this has also coincided with a concerted effort to increase minority representation.

“There are many more women on the faculty, there are many more people of color, many more marginalized people than when I joined,” Riley said.

Riley recalls there only being two faculty members of color in the journalism department when he joined.

“Now we have [faculty from] South America, Asia, we have representation from a very, real cross-section of international professionals, and we just hired someone who is of Chinese heritage,” Riley explained.

Riley said a lack of diversity in the media at large and in the staff at Emerson was something that the journalism department intentionally tried to do its part to correct.

“We take it seriously,” he said. “We have changed the complexion of our department a lot.”

This increased size and diversity are one part of what is a continued commitment to innovating the journalism department at Emerson, according to Riley.

“We work hard to stay ahead of the curve,” he said.