Enlisting the help of a hacker may be Erica Hill’s best hope for resolving their student loan debt.

Hill first stumbled on the idea on the internet, where people have proposed the possibility of a Robin Hood-type hacker erasing the national debt overnight, effectively forgiving millions of borrowers, although not legally.

“That’s the best-case scenario. I’m like, please hacker, come save us,” Hill said sarcastically.

One in six adult Americans has student loan debt, amounting to 43 million individuals, according to Congress. The collective national student loan debt balance is $1.814 trillion. From 2007, one year before Hill started school, to 2022, the average federal student loan debt had a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.94%. The total student loan debt balance nationwide grew 193.3% in this time.

Hill graduated from Emerson in 2011 with a Bachelor of the Arts in Film Production, along with minors in philosophy and religion, and women and gender studies. They started their undergraduate program in 2008, during the Great Recession. As they entered their college career, they were warned that finding a job after graduation was not guaranteed. Hill came from a small town in Connecticut, where job opportunities were scarce. They developed an early passion for filmmaking from making movies with their friends. Emerson was their dream school.

As a first-generation college student, Hill was mostly on their own when it came to choosing a school and navigating the finances of higher education. Already in a financially fraught situation, Hill worked throughout their time at school and lived below their means just to be able to afford materials for classes—only to graduate with $120,000 in debt in their name, and $25,000 more owed by their mother.

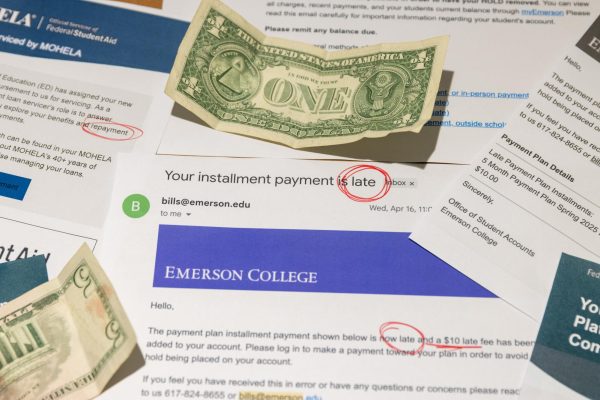

Like many Emerson students, Hill moved to New York City after graduating. Their loans kicked in a few months later, and they struggled to make payments and find employment. They got a job at a non-profit theater, hoping it would make them eligible for student loan forgiveness. That’s when they learned the nature of the student loan world—recertifications, interest rates that spike one year and nosedive the next, and caveats that give people less assistance than they need.

In the face of overwhelming payments and sparse job options, Hill decided to go back to school, hoping it would make them more competitive in the job market. Hill pursued a master’s degree in Library Education and Sciences at Simmons University and settled down in Boston, where they still reside today.

Now living in the city where they earned their education, Hill landed a job at a documentary company, bringing together their two fields of study—film and archival work. Despite landing a full-time job, they still struggled to navigate the rough waters of monthly student loan payments, subsidized versus unsubsidized loans, and variable interest rates—some of which were nearly 14%.

“It was such a nightmare. I couldn’t even try to focus on making movies and being a part of [the film] industry,” Hill said. “I was constantly on the phone with loan companies trying to figure out what I could do [and] how I could pay.”

Hill remembered the first time they saw their student loan balance go down after graduating. It was 2016, a year marred by fights with the Department of Education to let them take over a loan in their mother’s name because she was getting sick. Ultimately, the loan was discharged because their mom passed away.

“My mother passing away was one of the ways that I could actually pay off some of the debt,” they said. “Which is really kind of sad and disheartening.”

Even then, Hill still faced a balance of over $100,000. Another small wave of relief came in the form of the inheritance their mother left behind, which they put directly into paying off their debt.

“[It] took out a chunk of my debt, which I’m grateful for, but I wish I didn’t have to take losing a parent to do that,” they said. “I don’t think it should have to be that way for anybody.”

Today, a $25,000 balance remains—$4000 shy of the yearly cost of Emerson’s tuition in 2009—but between interest rates, recertifying, and “the rules changing every six months,” according to Hill, they don’t foresee paying off their debt until their 80s. According to Credible, nearly 3 million borrowers have at least six figures of debt to their name—which, depending on repayment, refinancing, and interest, could take anywhere from 10 to 25 years to settle, on average.

“I graduated a while ago, and it’s constantly on my mind how I’m going to pay it,” Hill, who is now 36, told The Beacon. “I don’t have any savings for a house, or a new car, or anything like that…even though I do have a really great job, a really stable job right now.”

This struggle is not unique to Hill, nor is it to Emerson graduates. According to the Education Data Initiative, 51% of student borrowers in the nation have not bought a home due to their student debt. Among those 49% who are homeowners, 29% delayed purchasing their homes due to student debt. Thirty-one percent of student borrowers delayed purchasing a car due to their debt.

“My mother passing away was one of the ways that I could actually pay off some of the debt, which is really kind of sad and disheartening.”

– Erica Hill, ’11

Yet the unpredictable nature of higher education, and student loan debt, does not discourage students from entering it—or even pursuing a career in it.

Stephanie Weber, who graduated from Emerson in 2024 with a degree in visual media arts, was excited when she learned that as an alumnus, she would be able to access Emerson’s library and texts after graduation.

Working in higher education, specifically under the alumni relations umbrella, Weber was drawn to the library access because of the academic resources and data she would be able to utilize. It was unique and helpful, something that made Emerson stand out in comparison to the alumni perks offered by Northeastern University, where she currently works.

But when Weber arrived on campus, ready to tap her ID and gain access to the Iwasaki Library once more, she wasn’t allowed in. She said it was another moment where she felt the familiar and not-so-distant feeling of disappointment.

“There was just a really big communication barrier between security and the resources that are offered to me as an alumni,” Weber said. “So eventually, I just stopped going because it was too difficult to actually access the resource.”

Because of her role at Northeastern, Weber is familiar with the inner workings of higher education and an alumni relations department. There are quotas to meet, calls to be made, and pressure to fundraise for the institution.

Later that year, when Weber saw the annual communications regarding Giving Day–a time when Emerson alumni are solicited for donations to their alma mater–she thought of her loan balance, and the library, and questioned whether the $25,000 she owes to her loan servicer signaled that she had already given Emerson quite a bit.

Currently, “there’s a lot of skepticism towards institutions and education in general,” Weber said. “So it’s really interesting that interests and loans are so much higher than they have been previouslywhen more and more people are attending university [each year].”

She recalls that in the days leading up to her commencement, members of Weber’s graduating class gathered in one of Emerson’s theaters to prepare for the upcoming ceremony. Sitting in the same seats where freshmen have convocation each fall, Weber remembered a member of the administration asking the students to raise their hands if they had a job lined up post graduation.

“I think maybe 10% of people raised their hands,” Weber said.

But this was no surprise. Weber, who now works a world away from her area of study as a program assistant in Northeastern’s student engagement and philanthropy program, had always felt disillusioned by the notion of the infamous “Emerson Mafia.”

“Every single time I’ve reached out to folks within [the Emerson Mafia], I’ve never gotten a response,” Weber said. “You kind of have to be in the industry to have that connection. And I’m not really an industry person.”

Hill, who graduated from Emerson 13 years before Weber, echoed the same disillusion with Emerson’s lack of preparing graduates for the financial struggles yet to come.

“It would have been nice to have a little bit more guidance [about], what our work [is] worth?” said Hill.

Citing the cost of attending Emerson, Hill spoke of an inequity once graduates enter their respective fields of study.

“If the tuition is this much and you’re selling these degrees like film production or theater or whatever, what is that in relation to how much we’re going to make in that industry? Because I still don’t really know,” said Hill.

In the VMA curriculum, Weber said she felt lost in the sea of resources at her disposal. After graduating, that feeling continues to bleed into her work.Weber said that after graduating she hasn’t used her degree.

“I have felt really uncreative,” she said. “My writing ability has totally fizzled out. I have these aspirations, but it’s not really happening,” Weber continued.

Matthew Pacione attended Emerson from 1990 to 1994, back when Emerson sat at the corner of Berkeley and Beacon Streets. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Communications with an emphasis in radio, which manifested into his involvement with WERS. Pacione spoke highly of the internships he landed, the urban setting Emerson students called home, and the lifeblood of campus that was the student body. He went to the Emerson Los Angeles program before the Hollywood Boulevard campus was built, living in Burbank and going to class on Olive Avenue. Pacione decided to stay in L.A. after graduating to try and make it in Hollywood, before deciding to pack up and leave the city in 2002.

“I don’t think it’s Emerson’s fault, but L.A. is a tough road…I never made over $35,000 in eight years post-graduation,” said Pacione. “So I left. I looked at the situation and said, ‘It’s not for me, I better re-evaluate.’”

During Pacione’s undergraduate years, Emerson cost $19,000 between tuition, room, and board, with $12,000 of that total accounting for tuition. Adjusting for inflation, that equates to nearly $47,000 today.

“That was a lot back then. Obviously, it’s jumped tremendously now, which is kind of my big gripe with Emerson. It’s jumped almost four times the amount,” he said. Today, Emerson’s sticker price of tuition, room, and board is roughly $80,000 per year.

Choosing an alternate path, Pacione took out loans through a local bank rather than a federal program. Originally from a suburb north of Boston, he lived with his parents his last two semesters before L.A. and took a 20-minute commuter rail ride into the city every day. For the first three and a half years after graduating, he had a student loan payment of $240 a month with a 2.5% interest rate. It took Pacione twenty years to pay off.

Pacione said he knows his situation is brighter than most, but it didn’t come without struggle. His payments delayed him in becoming a homeowner, hindered him from settling in one place sooner, and sometimes even impeded his ability to meet daily needs, like gas.

“There were many times, too many to count, where I would look at my budget at the end of the week, end of the month, and I had $10 left,” he said.

In 2014, Pacione was able to call himself debt-free from student loans for the first time, and he used this newfound freedom to buy a home, 22 years after graduating from college. Now, nine years later, he has obtained a master’s degree at Norwich University in Vermont and is putting his two children through school at the University of Washington. He said he purposefully avoided Emerson in both his master’s and his children’s pursuits of higher education due to the cost.

“Several alumni my age say, ‘I can’t afford Emerson.’ There’s no way I would send my kid to Boston, Los Angeles, etc. for $300,000 for four years,” he said. “Think about that cost for a minute. That’s a house. That’s a really deep commitment.”

According to the College Board, Emerson’s average price after aid is around $50,000, with 48% of students receiving financial aid in some form.

In the past couple of years, Emerson’s tuition has experienced steep increases. For the 2022-2023 academic year, tuition rose 2%. The following year, 2023-2024, a 4% hike was announced. This trend continued the last two academic years as well, with a 3% hike in the 2024-2025 year and a 3.5% hike this year. In 2023, the Princeton Review ranked Emerson College number one worst in the country in terms of financial aid options.

Emerson is not the only private liberal arts institution where students are forced to foot a hefty bill. Compared to other schools of this nature, the $57,056 annual sticker cost of tuition and fees isn’t out of character. Northeastern’s tuition and fees are $66,612, Boston College’s are $70,702, and Suffolk’s are $47,550, as The Beacon has previously reported.

Pacione’s dissatisfaction with rising tuition and the insurmountable burden of student loan debt represent a greater issue, he said: an “out of touch” governing body and a lack of “return on investment.”

“I just think Emerson keeps having expenses after expenses without thinking of the student debt. At some point, you’ve got to stop raising expenses,” he said.

But for Hill, the problem is two-fold.

“Part of the reason they’re laying off [staff] is declining enrollment, but part of the declining enrollment is the cost of tuition,” said Pacione. “They’re not looking at the root cause of the problem.”

In August, Emerson laid off 30 staff members, citing declining enrollment and budget reduction. The college also announced it is seeking to downsize full-time faculty through a Voluntary Separation Incentive Program. Boston University also announced the layoff of 120 staff members over the summer, and other private institutions nationwide are making similar cuts due to revenue falling short of projections.

The financial challenges of being a private institution and the national landscape of higher education only further complicate this issue. President Donald Trump’s sweeping legislative package, passed in July, seeks to resume loan collections from past borrowers, cap the amount borrowed for Parent Plus loan holders, and restrict student loan forgiveness. Additionally, the prospect of another economic recession and the federal government’s growing attention on higher education institutions have alumni like Hill fearing that the current political climate might discourage some from pursuing college altogether.

“Anytime I’m hearing about something about the current [presidential] administration in regards to student loans, I’m just like, ‘I don’t think you have any idea what’s going on.’ I think it’ll prevent some people from going to college,” said Hill.

“There were many times, too many to count, where I would look at my budget at the end of the week, end of the month, and I had $10 left.”

– Matthew Pacione, ’94

But the polarized political atmosphere did not discourage Gabriella Collin, class of 2024, from pursuing a degree at Emerson with excitement and energy.

Collin, a comedic arts graduate, remembers the sheer pride and joy they felt upon learning of their acceptance to Emerson. After applying and getting waitlisted, an Emerson acceptance letter was the end result of a long-fought and relentlessly pursued goal.

Rose-colored glasses now tossed aside, the memory is nearly tarnished for Collin, who likens their almost $100,000 in debt to that of a scarlet letter.

“I worked so hard. I was just so happy that I had gotten to where I wanted to be—my dream school,” Collin said. “I wasn’t paying attention [to the loans] because I had finally gotten the thing I had spent four years working towards.”

Collin, one of four siblings, could not recall what amount of financial aid they received from the college, but they do remember feeling disappointed by the amount.

“Financial aid officers don’t care that you have younger siblings or other family members,” they said. “You’re the customer. They’re trying to sell you the best deal they can.”

Having worked throughout their entire college tenure to afford groceries, textbooks, other necessities, and the occasional night out, Collin’s transition to post-graduation life carried few surprises. But just months after commencement, the loan balance, in addition to rent and other cost-of-living expenses, began to pile up. And so did the pressure to find a steady, reliable income in an unforgiving job market.

“It’s kind of like an inverse lobster trap, where people are constantly getting let out, but no one’s getting let back in,” Collin said. Splitting the hours between their job at the Garment District, a Cambridge thrift store, and the Improv Asylum comedy club, Collin works full-time but makes just $19 and $15 an hour, respectively. In the hunt for a job in their desired field, the balancing act of finding the right fit has been tricky.

“Something I’m always thinking about is salary [and] distance,” they said. “How much of my life am I willing to uproot, to pay this thing that’s taking over my life?”

But what frustrates Collin most is their newfound lack of pride for Emerson, a complete 180-degree turn in perspective from the days of their acceptance letter.

“With my debt, and the debt of other people that I know and care about, seeing the way the school is kind of caving in on itself, I just get so mad,” Collin said. “I want my money back, and I think a lot of people feel this is not what I signed up for.”

Despite their recent grievances with Emerson as an institution, Collin has accepted that their student loans, however intimidating, will ultimately be paid. Their real concern lies beyond the walls of Emerson. Now, they worry about how the weight of the $100,000 debt on their shoulders could affect others, specifically their 16-year-old sister, who dreams of attending Fordham University in the Bronx.

“The last thing I would ever want for her is her education to be affected by my financial burdens,” Collin said. “I think a lot more about my family at large, just feeling bad for them. I’m like, ‘I’m sorry for this to happen.’”

For Hill, the cost is more than financial—it’s mental, too. Their free time isn’t spent making art, experimenting, or “playing” with different ideas for films. Post-graduation, their bills dictate the way they spend their time.

“It’s kind of changed how I spend my time, because my job is the main thing I schedule everything else around,” they said. “The student loan debt is… something that just perpetually hangs over my head.”

If they could go back, they said, they would have chosen a different path.

“I would’ve figured out some other way to make it cheaper for myself,” they said, noting that friends who went to MassArt, a public school, have paid off their student loans

Despite this, Hill doesn’t take for granted the relationships that Emerson gave them that they still maintain.

“I did make a lot of connections at Emerson, but I think the sustained relationships with those people have come from our mutual disappointment in our overall experience at Emerson,” they said.

If their student loans were to disappear tomorrow, Hill said, they would feel they could finally do the things their parents did in the 1990s while working regular jobs.

“I would be able to save for a house,” they said. “I think it would definitely allow me to build up savings, which I currently do not have.”

For now, the student loan payments keep coming, even at the cost of Hill’s peace of mind.

“Even though I am making the most money I’ve ever made, I am living paycheck to paycheck,” Hill said.

Want to share your opinion on this article? Submit a letter to the editor at berkeleybeacon@gmail.com.