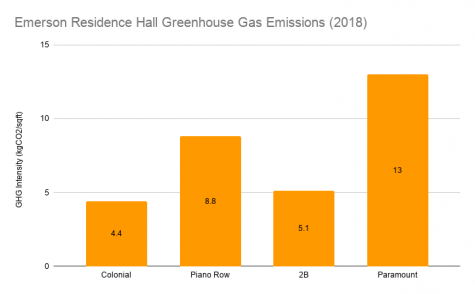

Of all of BostonŌĆÖs residence halls, The Paramount Center produces the most greenhouse gas emissions compared to its size, according to data gathered in 2018 and published in September 2019 by the City of Boston.

In 2018, Paramount produced 13 kilograms of carbon dioxide per square foot, totaling nearly 2 million kilograms of carbon dioxide, according to Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance data. This is equivalent to driving over 4 million miles in the average car, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Comparatively, Simmons UniversityŌĆÖs Evans Hall only produced 1.2 kilograms of carbon dioxide per square foot, the lowest rate among Boston residence halls.┬Ā

Paramount, which houses approximately 260 students, is the only Emerson residence hall that is not LEED-certified. LEED certification, which is given by the U.S. Green Building Council,┬Ā gauges the environmental friendliness of the technology and construction of buildings. Piano Row, which is LEED Silver certified, trails closely behind Paramount in greenhouse gas emission intensity at 8.8 kilograms of carbon dioxide per square foot, followed by 2 Boylston Place and then the Colonial Building. The data for the Little Building is not yet available, but the college is attempting to secure the top LEED certification.┬Ā

The Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance requires all of BostonŌĆÖs large- and medium-sized structures to report their energy and water usage yearly in hopes of lowering greenhouse gas emissions by 15 percent every five years, according to a BU News Service article.

The Paramount Center received its latest renovation in 2010, making it the least renovated residence hall on campus.

Although Paramount was the residence hall that emitted the most greenhouse gasses relative to building size in Boston in 2018, Berklee College of Music residence halls had on average the highest intensity of greenhouse gas emissions in the city.

Campus Sustainability Manager Catherine Liebowitz said the reason for ParamountŌĆÖs sustainability shortcomings is that its last renovation was in 2010. Since the college renovated 2 Boylston Place and the Little Building more recently, Liebowitz said the college utilized more sustainable building materials.

ŌĆ£LEED certifications were around, but [they werenŌĆÖt] something that was necessarily the standard,ŌĆØ Liebowitz said. ŌĆ£There are definitely things that were taken into account to make it a greener building, but it wasn’t a priority at the time.ŌĆØ

Duncan Pollock, associate vice president of facilities management,, said Paramount currently utilizes some green technologies, such as using LED bulbs and the green steam system, which delivers thermal energy to Boston buildings. Pollock said compared to the other renovation projects on Emerson residence halls, the Paramount renovation didnŌĆÖt lend itself to massive green overhauls.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It wasnŌĆÖt what we call a gut renovation, where you tear everything out and rebuild everything,ŌĆØ Pollock said. ŌĆ£It didnŌĆÖt allow for us to do more sustainable projects.ŌĆØ

Paramount also houses two theaters, which Liebowitz also cited as a contributing factor to its high energy usage. Liebowitz said various green updates to Paramount are in the works, including LED bulb upgrades, installing an energy analytical system that adjusts energy load to maximize efficiency, and electricity load-shedding that shuts down certain systems when others are in demand. However, the college has yet to implement any of these changes.┬Ā

ŌĆ£I don’t want to say there’s anything set on a specific timeline, because that isn’t true,ŌĆØ Liebowitz said. ŌĆ£But everyone is aware and everyone is definitely interested in making those green updates.ŌĆØ

Despite this data, Liebowitz said Emerson has reduced direct carbon dioxide emissions by 80 percent since 2007, despite campus size increasing by 60 percent per square foot.┬Ā

Senior Raven Devanney, co-president of on-campus environmental advocacy group Earth Emerson, told The Beacon she is frustrated that the housing requirement compels students to live on campus for three years in spaces that often have significant carbon footprints.┬Ā

ŌĆ£As a student, you want to know what your impact is, especially since EmersonŌĆÖs changed their housing policies,ŌĆØ Devanney said. ŌĆ£To not have that information to know exactly what each building is doingŌĆöit’s kind of frustrating because it kind of takes the agency away from the students.ŌĆØ

Liebowitz said she understands student concerns over the sustainability of the campus they live on and urges them to voice their opinions to college officials to spur change.┬Ā

ŌĆ£I get that there can be a lot of frustration, and it’s trueŌĆöyou don’t always get to choose your setup of where you’re living,ŌĆØ Liebowitz said. ŌĆ£But you’re in an environment that is very open to feedback.ŌĆØ

Devanney said she wishes the campus would prioritize greener building decisions, even if it means sacrificing comfort or aesthetic.

ŌĆ£It is so cool to see the flashing lights on the Paramount building, but what would happen if we turned those off for a month?ŌĆØ Devanney said. ŌĆ£Would it look as cool? No. But is it going to look cool in 10 years when the world is on fire? No.ŌĆØ