Two alumni created an immersive art installation that brings viewers into an uncanny, uncomfortable, and vulnerable experience of stepping into a stranger’s most intimate space.

M’Kenzy Cannon, a visual and media arts graduate, and Maya Rubio, a business of creative enterprises graduate, are the proud creators of “Please Let Me In,” available for viewing in the Boston Center for the Arts until Sept. 15. The exhibition is part of BCA’s 1:1 Curatorial Initiative—a series of collaborative projects between one curator and one artist. Its purpose is to introduce a new artist or to highlight a new aspect of a more experienced artist.

An open call for this initiative came out not long after Rubio and Cannon graduated in 2021. This inspired Rubio to reach out to her former classmate and curate this installation.

“I saw [this] opportunity and I had just watched [Cannon’s] BFA film, and I was like ‘Woah, [Cannon] and I could do something,’” Rubio said. “We weren’t really calling ourselves artists and curators yet, but I felt like we could at least make a proposal.”

Prior to Rubio reaching out, Cannon had been working on her own projects. Upon learning of the initiative, however, she discovered a way to use past projects to create an installation with a larger idea.

“I’d been collecting dream recordings from my friends and some strangers,” Cannon said. “I’d also been doing an archival project, archiving photos that I’d found on Craigslist and Zillow. It felt like there was a way to pull all of these things together to create a larger installation show [displaying] that intimate experience of seeing the interior of people’s homes [and how it] can provide such a voyeuristic insight into someone’s life.”

Both Cannon and Rubio find inspiration and joy from theatre, and during their junior year at Emerson, found a way to combine this with their shared love of art. These two passions later became the inspiration behind “Please Let Me In.”

“[Cannon and I] took a class together junior year called Living Art in Real Space, and that was the first time that we had experimented in installation and performance,” Rubio said. “That gave us confidence to make something and [we] knew that we loved that process. We both really connected with going back to that performance vibe and connecting that with our greater art pieces.”

In order to create a living, breathing exhibit from just a concept, both Rubio and Cannon spent months meticulously constructing and deconstructing ideas to perfect their imperfect world. To create a space in which the audience could feel fully immersed, they needed to balance visual art with theatrical performance.

“It was really important for us to break down the space into different zones and really just think about the worlds that we were trying to create instead of focusing so much on the certain objects, and once we built the different worlds, we knew that the work and the objects would emerge,” Rubio said.

Through their combined use of photography, video, 3D elements, and performance, they provided themselves with more opportunities for creativity and freedom.

Bedroom portion of the exhibit “Please Let Me In.”

“It was very freeing for me, as someone who works primarily in film and video, to be able to extrapolate these kinds of cinematic ideas into physical objects and physical experiences,” Cannon said.

The installation is described on BCA’s website as “a piece of object-spatial theatre, an environment performance in which gallery-goers become a character in the sticky world of existential mystery.” As the gallery-goers venture deeper into the belly of what this exhibition is all about, they find glimpses into the mind and life of one stranger—and potentially themselves.

The tables and shelves littered with various knick-knacks from lives and childhoods create a stark contrast between the bleak, white walls of the venue.

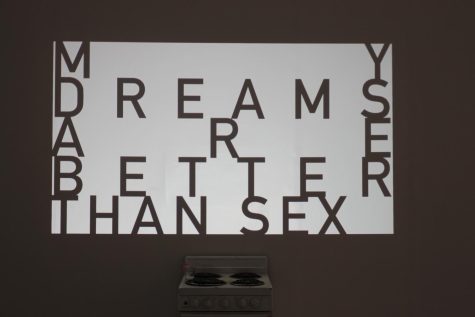

Multiple projectors spark life on the once-bare walls, displaying a carousel of uncanny images showing various rooms in someone’s home. Another projector displays phrases and thoughts that are usually only found within the psyche.

“My dreams are better than sex,” one reads.

A monitor displays the words “my dreams are better than sex.”

In another corner of the room are piles of mulch, but upon closer look, pieces of junk can be seen scattered and buried in the dirt. For the audience, however, there is much more to be discovered within the debris.

Does the mulch represent the burial of memories in the unconscious mind, the scraps representing the memories themselves? Does it serve to create a nostalgic feeling of playgrounds and childhood that’s been littered with the trash of reality and adulthood?

Each viewer is left to find their own answers, and that is exactly the point of the exhibit.

The exhibit’s features create a sense of existentialism as viewers find themselves in what seems to be the memories and mind of a stranger. The section of hanging photographs allows for small glimpses into this stranger’s life.

As viewers continue to venture into the past and present of the subject’s mind, the exhibit gives way for them to ponder their existence and dread their future.

Further into the exhibit sits a bedroom untouched by time, littered with the evidence of a stranger’s presence. A diary lays open on the bedside table and toiletries lay on the shelf, half used.

A book and diary lay on a desk of the exhibit.

A bedroom is often seen as a person’s most private space, but this bedroom offers the whole tale of someone’s life. Without the room’s owner present, the audience must piece together the details themselves. With hints of childhood, tragedy, and the mundane, viewers are forced to examine what makes a person who they are, and how the space around them chronicles their story.

Uniquely, this exhibit not only shows the audience a piece from the artists’ perspective but also transports them into the installation.

“I want our audience to feel confronted with something unique,” Rubio said. “The experience of entering a zone and a space that transports you and puts you in touch with some of those memories you haven’t touched in a while…is a really successful kind of encounter.”

Cannon found the exhibition of the bedroom to be the most stimulating to audiences.

“In general, the purpose of the show was to provide people with the opportunity to experience something uncomfortable, especially the bedroom piece,” Cannon said. “[It is able to] provide people the opportunity to scratch the itch of snooping around a stranger’s intimate space. That was a very palpable, emotional thing I wanted people to be able to release and take part in.”

Rubio found it important to curate the exhibit as an environmental performance due to the unique situation it puts audience members in.

“[Cannon and I] are very interested in disrupting a traditional gallery experience, but we didn’t want the show to feel like objects on a wall that feel distant from the viewer,” Rubio said. “The goal was to have this emotional environment where when your body is inside of this space, you become a part of the space. Your thoughts and personal histories and form bring the space to life.”

Crafting an immersive installation creates a different experience compared to traditional art galleries.

“Gallery exhibitions and museum exhibitions, have this stark ‘hands off,’ kind of distance between you as an audience goer,” Cannon said. “I wanted people to be able to break that wall down and take part physically in the piece, because the living room piece with the shells and the objects, and the bedroom piece don’t work without that physical interaction.”

To Cannon and Rubio, the installation is less of a gallery and more of an attraction.

“We wanted to think about it as a truly immersive, theatrical world that you step into,” Rubio said. “It achieves an emotional impact, kind of like a haunted house in terms of stepping into a new world.”