The public art installation “What Do We Have in Common?” concluded its run on Boston Common Sunday after a month of prompting passersby with questions about ownership.

The installation, a large cabinet with drawers of questions for audiences to open over the course of 32 days, was placed on the Common on Sept. 22 by NOW+THERE to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Friends of the Public Garden. The project’s curator, Erin Sunderland, said that while the striking appearance of the installation drew much attention, she considered it a success because of its ability to prompt introspection.

“From the artist’s perspective, she was looking to create a provocative, beautiful work which explores questions about things such as who owns common resources,” Sunderland said. “The idea was to invite all people to talk about commonalities and public ownership in the Boston Common, which is the nation’s oldest public park.”

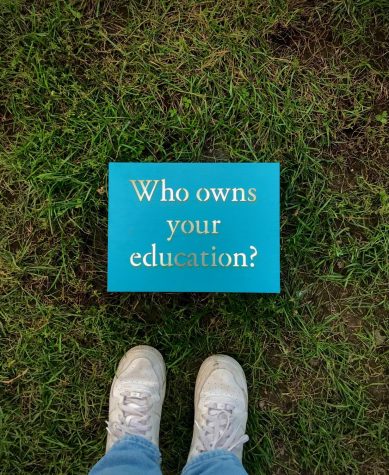

The placement of the installation on Boston Common was a strategic choice, as it was the perfect place to pose big ideas in a casual setting, according to Sunderland. Passersby unknowingly wandered onto the exhibit not expecting to find an artwork that challenges many conventional societal ideas such as who owns the laws, education, or the moon.

One of the many questions of the art installation.

“I remember seeing it in the common and being curious about what it was, because it wasn’t clear that it was an art installation,” junior theater education student Amanda Di Benedetto said. “It was just a big box in the common, and it became more apparent as you got closer that it was an art piece.”

Once at the installation, questions were written on plaques around the ground and in a large cabinet at the center of the exhibit. One of the most impressive factors of the art piece was that it was designed for people of all backgrounds to partake in.

“There were a number of questions in other languages as well,” Sunderland said. “Actually, 32 of the 200 questions were in Spanish, Hatian Creole, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese, and Cape Verdean Creole. The idea behind that was to make the questions more accessible for everyone in and around Boston, because those are the other major languages spoken in the city.”

Before conversations on ownership even began, the inclusive art piece made an impact on audiences by making them more aware of the diversity in the city.

“Around the common, they would have a question in English, and then have the same question in Spanish or Mandarin,” Di Benedetto said. “In addition to this, all of the people working there are bilingual. It helped me realize and understand that there is more than just my point of view. There’s bigger things than just me; there are other people and other cultures.”

At the exhibit, “guides” were responsible for facilitating conversations and ensuring that audiences got the most out of the exhibit. Their job was to take very difficult and daunting questions and make them a little easier to comprehend, Sunderland said.

“First, the guide asked me who owns the moon,” Di Benedetto said. “At first I thought, I don’t know, does anyone own the moon? It’s just the moon. The guide told me that people told her that America owns the moon because they have a flag on it, but others said nobody should own the moon at all.”

“She made me realize that it’s about the things that we own together, or how we can get to owning those things or nobody owning things,” she continued. “ It was eye opening.”

Sunderland said that without the guides, the success of the installation would not have been possible.

“They were really engaging to everyone on the common and started some really interesting and engaging conversations,” she said. “From my perspective, that was one of the best things about it. Based on the press response and social media response, I would definitely say the installation was successful in generating conversation.”

Di Benedetto urged others to consider the message of the installation regardless of if they attended or not.

“We should start to think about things that we own together or things that nobody owns, or things that some people do own but maybe everyone should own,’” Di Benedetto said. “The point of it was to walk away knowing, ‘I think this, and you think that, but together we are both talking about the same thing and can come to an agreement on what we believe. We need to be more accepting, more willing, and more open to change.”