With inflated workloads, slashed benefits, and continuing tense negotiations with Emerson,┬а college staff members are nearing a breaking pointтАФafter more than a year of sacrifice forced by the pandemic.┬а

Emerson staff membersтАФboth the 1,210 directly employed by the college and its third-party vendorsтАФquickly shifted their focus to provide the community with safe classrooms, educational resources, and food in their stomachs when the college abruptly moved classes online last March. Since then, they have worked relentlessly to keep the college running behind-the-scenes.┬а┬а

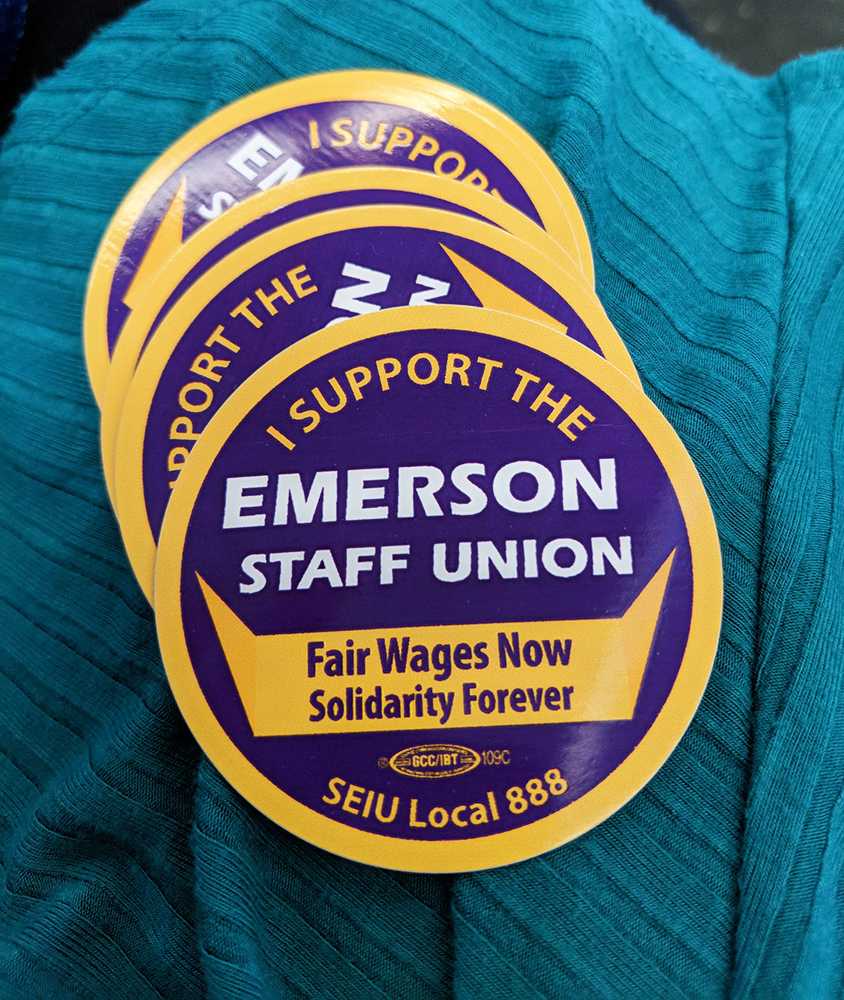

After the campus abruptly closed, the staff union negotiated with college administrators to prevent staff layoffs for the duration of the fall semester. In return, staff members agreed to take benefit cuts and forfeit all raises to combat the projected $33-76 million COVID-19 related losses over the 2021 fiscal year.┬а┬а

Since December, the union has made a push to get back some of the sacrificesтАФlike benefit cuts and a raise freezeтАФthey made in an effort to assist the collegeтАЩs financial standing and preserve their jobs, Staff Union Chair Dennis Levine said. Now that Emerson is anticipating a тАЬbest-case scenarioтАЭ financial loss of $30 million, slightly below initial predictions, Levine said the reinstatement of staff benefits is due.┬а

тАЬWe have to start worrying about things that are going to happen next semester,тАЭ Levine said. тАЬOur members have lots of concerns, financially we’re helping the school, but the school is not really doing us any favors.тАЭ

In the unionтАЩs 2018 collective bargaining agreement, staff are guaranteed an annual 3.9 percent raise. However, with the pandemic continuing to decimate staff membersтАЩ finances, Levine said it has become more imperative employees receive immediate monetary relief.┬а ┬а

In that collective bargaining agreement, the staff union fought for a тАЬsick bank,тАЭ where employees can donate paid sick days to other staff who may have used up theirs. This programтАФwhich Staff Union Vice-Chair Shaylin Hogan said the college fought fervently againstтАФhas proven essential during the pandemic.

тАЬPeople may have lost their second job and now all of a sudden you’re out sick and you have no vacation time or sick time left,тАЭ Levine said. тАЬHow are you supposed to support your family, are you supposed to pay your bills and keep the heat?тАЭ

The Emerson Staff Union is hoping to have some of their sacrificed benefits reinstated, especially for some of the at-risk staff members.

Administrators have given them no indication during negotiations when this raise, among other benefits, will be restored.┬а

тАЬThey say we might be flexible, we might be changing, but there hasn’t been any kind of promise or anything like that,тАЭ Hogan said. тАЬThat’s really hard to hear when we know that we’ve kept the school going this long without having to be on campus all the time.тАЭ

Vice President for Administration and Finance Paul Dworkis said in a November faculty forum outlining the collegeтАЩs tentative positive financial outlook that reinstating benefits was premature.

тАЬWe are too early in the fiscal year to be able to consider reinstating retirement contributions or pay raises,тАЭ Dworkis said. тАЬI want to thank the CollegeтАЩs staff and faculty unions for their partnership in establishing the cost-cutting measures that have helped us project jobs.тАЭ

Along with the financial sacrifices, staff also gave up two-and-a-half days of vacation time. This week, the college granted each staff member two vacation days that can be taken between March 22 and April 30, contingent on the approval of department managers.┬а

тАЬWe can only use them during what is, for most people, the busiest part of the year, not just the semester but the whole year,тАЭ Hogan said. тАЬI know it is very unlikely that I would be able to effectively use those days off for vacation because if I take a day off the next day, I still have to do all of my work for the day and the day before.тАЭ

The staff union doesnтАЩt afford protection to third-party staff, such as EmersonтАЩs food service workers, who are hired through food management company Bon App├йtit. Yet the pandemic forced them to adapt to an entirely new approach towards cooking, serving, and cleaning.

One Dining Center worker, who spoke through an interpreter on the condition of anonymity,┬а described taking time off at the beginning of the pandemicтАФbefore the college announced its shut down on March 13тАФand said she only returned because of the collegeтАЩs rigorous testing program and safety protocols.

Despite being vaccinated, the anonymous worker said her concerns over COVID caused her to limit her workdays at the Dining Center to three a week. The anxiety-inducing effect of the virus, she said, is just as psychological as it is physical.

тАЬPeople donтАЩt feel well even if they donтАЩt have it,тАЭ she said. тАЬThe first thing the virus attacks is the nerves.тАЭ

Students entering the dining hall.

Facilities management Crew Chief John Vanderpol said the disastrous state of the resident hallsтАФfilled with trash left by students rushing to leave in the springтАФforced staffers to work┬а nearly the entire summer to sanitize them. Now, VanderpolтАЩs responsibilities include sanitizing dorm rooms in Paramount with a Clorox 360 machine after students who test positive move out.┬а

тАЬWe know which rooms in the Paramount are positive cases, they give us the minimum of 24 hours or more, where they get out to go back to their dorm,тАЭ Vanderpol said. тАЬWe know that everything we’re touching or breathing, there’s a risk.тАЭ

Vanderpol said he worried about bringing the virus home to his family.

тАЬEvery day since March, so it’s always a thought, all the time,тАЭ he said. тАЬBut the college, they were very good at guiding. It seemed very organized.тАЭ

Electronic Resource Coordinator and Reference Librarian Daniel Crocker said straddling the pandemic with his personal life has been a major challenge.┬а

тАЬThe biggest source of stress is what do I do with my kid,тАЭ Crocker said. тАЬThe fact that we had to make the sacrificeтАФeveryone who made it understood it. We do feel a little deceived about those raises. Some unions on campus got a raise and some didn’t. But the financial strain of the pandemic is the least stressful part. Money is tight. It was tight before. it’s always been a little tight at Emerson.тАЭ