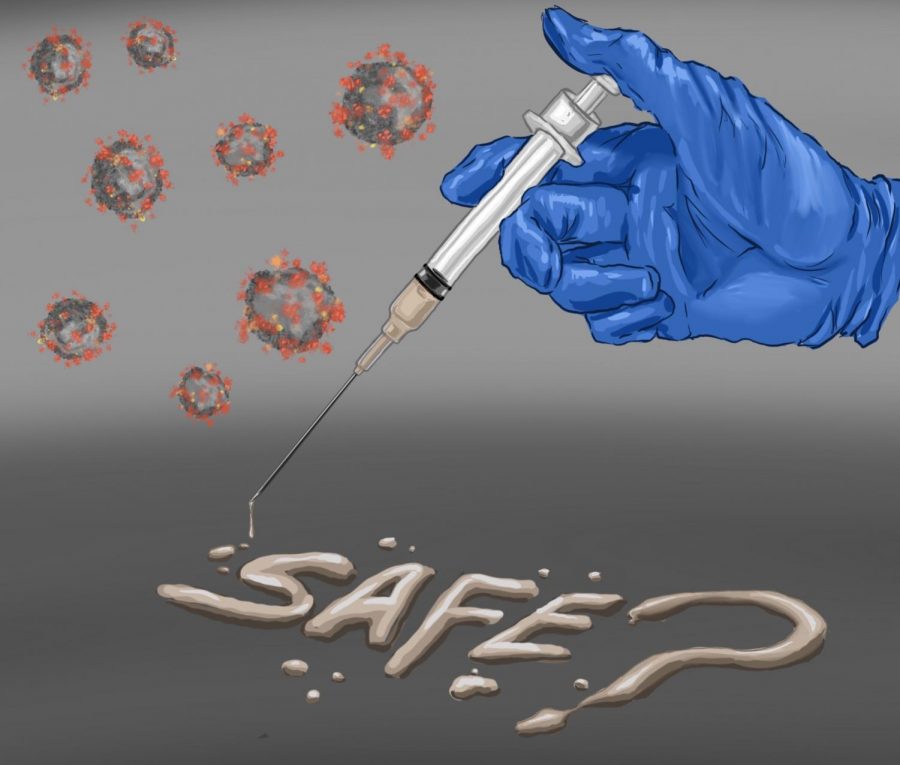

Amid a pandemic that has taken 1.96 million lives and is set to infect many more, the world anxiously awaited a vaccine. Vaccines typically require years of development before reaching the clinic, but the events of 2020 forced scientists to speed up and produce a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine by this year.

Because of this, we saw much skepticism on the effectiveness and safety of a COVID-19 vaccine. The Pew Research Center showed in September of last year in a survey that only 51 percent of U.S. adults indicated a willingness to take the vaccine.

The Washington Post claimed that “a lot of this mistrust is likely to be a result of recent attempts, especially by President Trump and his aides, to interfere in the scientific and regulatory review process.”

However as Trump’s presidency comes to a show-stopping end, confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine rose to 60 percent who claim they “will definitely or probably get a vaccine for the coronavirus,” according to another Pew Research survey.

As 2020 wrapped up, on Dec. 18 Federal regulators gave emergency approval to vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, both of which require patients to receive two doses spaced weeks apart. These have been described as possessing “remarkable initial efficacy” by STAT.

Biotech company Moderna announced the final results of the 30,000-person efficacy trial for its candidate in a press release on Nov 30. Only 11 people who received two doses of the vaccine developed COVID-19 symptoms after being infected with the coronavirus, versus 185 symptomatic cases in a placebo group. This is when volunteers are randomly assigned to either a test group receiving the experimental intervention or an inactive substance that looks like the drug being tested.

According to the New York Times, only 3.1 percent of the American population has received the vaccine, and only 10.3 million vaccines have been distributed so far. Every state was granted an amount of the vaccine roughly in proportion to its population. Data from clinical trials of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines suggest they prevent symptomatic COVID-19 infection in roughly 94.1 percent of people vaccinated.

It’s important to note that the trials being conducted to test various vaccines can’t tell us whether they prevent infection, only whether they prevent symptomatic infection. Nevertheless, Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine was initially judged safe for use in the UK and now in the United States.

Knowing that there is a higher probability of a positive reaction to taking the vaccine, why is 39 percent of America so suspicious?

For starters, President Trump’s efforts to pressure the FDA to issue an “ Emergency Use Authorization” before the Nov. 3 election — before the vaccine trials were finished — deepened a sense of distrust. A survey conducted in December of last year showed that of 2,000 doctors and nurses in New Jersey, although 60 percent of doctors planned to take a COVID-19 vaccine, only 40 percent of nurses intended to.

This unease is also particularly high among Black and Latinx communities. A Pew Research Center poll released in mid-September indicated 32 percent of Black adults said they were definitely or probably going to be vaccinated. This is worrying given that people of color are being infected and dying at a disproportionately high rate in the pandemic.

Health officials fear that “public adoption” will be crucial in stopping the spread of the virus. NBC states, “Experts say there isn’t an exact threshold for the percentage of people that need to get vaccinated to stop the virus’ spread, but it is expected to be at least 60 percent of the population.”

Even more worrying is as the virus rampages through America, with 4000 deaths across the country in a day in early January, fewer people are inclined to take a vaccine. A poll from the Pew Research Center published in September found a significant decline from May to September in people who said they would get the vaccine if it were immediately available. A lot of this is due to the spread of misinformation through right-wing media.

A report by the London-based nonprofit organization ‘Center for Countering Digital Hate’ found that the anti-vaccination movements have gained about eight million followers since 2019. According to a new report from First Draft, a global nonprofit organization that researches online misinformation, conspiracy theories on the COVID-19 vaccine have flooded Instagram and Facebook.

The Washington Post recently reported that even though former Vice President Mike Pence was seen taking the vaccine, many of Trump’s high-profile allies, including his former attorney Sidney Powell, have pushed misinformation. Claiming that the government will force people to receive a vaccination or use the vaccine to conduct surveillance of the population.

Another astounding factor to a consistent mistrust in the vaccine is the current deep distrust of the government. As we saw in the first week of 2021, there is a high level of chariness in the US government, and so much of it lies within political spheres. A survey released this week by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 42 percent of Republicans said they would definitely or probably not get vaccinated, as compared with 12 percent of Democrats.

Of course, Trump’s refusal to take the vaccine has not helped matters. Sheryl Gay Stolberg, a correspondent covering health policy wrote in The New York Times in December, “One reason for the partisan divide over vaccination, experts said, is the president himself.”

Trump’s repeated denigration of scientists and insistence that the pandemic is not a threat, Stolberg said, has contributed to a sense among his followers that the vaccine is either not safe or not worth taking. Matthew Motta, a political scientist at Oklahoma State University who studies politics and vaccine views stated in the NYT story, “We need [Trump] taking a proactive role.”

The mass conspiracy theory that the vaccine contains a microchip allowing the government to track people has spread ever since news of the vaccine surfaced. There is a plethora of widely shared videos and viral posts on social media, baselessly claiming that such technologies could find their way into syringes delivering shots. A YouGov poll suggested that 28 percent of Americans believe that Bill Gates wants to use vaccines to implant microchips in people—with the figure rising to 44 percent among Republicans. These rumors have been debunked by Mr. Gates himself, who told the BBC that the claims were “false.”

However, vaccine development breakthroughs during the pandemic have been nothing short of extraordinary. It is true that a few years ago, the notion that the world could start vaccinating against a pandemic like COVID-19 within a year would have been considered unlikely. But for desperate times come desperate measures.

According to STAT, vaccine makers compressed clinical trials, running Phase 1/2s or Phase 2/3s instead of the normal sequence of three phases with pauses in between. With the help of several partners like the—U.S. government’s Operation Warp Speed and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations and the Gates Foundation — batches of vaccines were produced and stockpiled before they were yet proven to work, shaving months off the time to vaccine deployment.

Cases have been rising nationally since September, from an average of about 35,000 cases a day to more than 250,000 cases daily. We need to work together to stop this spread, and that starts with understating what this vaccine can do. Experts say that “herd immunity”— the point at which enough people are immune that the spread of a virus is diminished— can be achieved when roughly 75 percent of the population is vaccinated. By continuing to maintain social distancing, wearing masks and proper hygiene, this pandemic can be fought, taking into account that our next step as a country is the vaccine.