Several students who spent time in Emerson’s quarantine housing during the spring semester have reported inconsistent protocol communication, faulty facilities, and meager food provisions—painting a picture of the college’s quarantine experience as one of profound institutional abandonment.

Approximately 110 students have been relegated to the Paramount residence hall this semester. The residence is reserved for students in isolation (who are known or reasonably known to be infected) and quarantine (who may have been exposed to the virus). Completely alone and cloistered from many of the college’s services, many of the students sequestered in Paramount—some battling COVID-19 symptoms—repeatedly lacked vital information only the college could provide, like release dates, laundry, and trash pick-up schedules. In other cases, they were volleyed from department to department in search of answers, lacking a streamlined process.

When first-year theatre and performance major Katie Broderick got the call that she tested positive for COVID-19 on Feb. 11, she texted everybody she considered a close contact. First-years Lily McCormick, Nathalie Calvillo, and Alaina Reyes, three of her close contacts, waited for calls from the college. They never came.

“Our assumption was we’re going to hear from contact tracers, we’re going to get contacted by Massachusetts and Emerson, so for the first few hours we were like, ‘Let’s hold tight, we should get calls any second now,’” Calvillo said. “When that didn’t happen, we decided to email and reach out and tell them.”

The students had to decide for themselves to hole up in their rooms.

“No one had told us ‘Don’t go anywhere,’ and … I feel like there’s other people that probably would have not done that,” McCormick said.

Calvillo was the last one to arrive in Paramount that day, following a dark walk in the freezing cold at 8 p.m. It wasn’t until the next day that the college reached out to them.

“We didn’t get calls from Emerson until the next morning,” Calvillo said. “They called us and said, ‘Did you know that you have been in contact with somebody who tested positive?’ And, I said, ‘Yeah. I’m in isolation.’”

First-year Nathalie Calvillo

The time elapsed between Broderick’s positive test and the call from Emerson was worrisome, Calvillo said.

“It’s in human nature to wait until Emerson does something and reaches out to you, because they’re in charge of us—we were supposed to trust them,” she said. “You would think that they would handle it. That’s where the risk is: We’re not getting contacted until too late.”

Close contacts—who have the potential to drive virus transmission—are contacted depending on what time of day the positive test is identified, Jim Hoppe, vice president and dean for campus life, said. Erik Muurisepp, assistant vice president for campus life and “COVID Lead,” said the contact tracing timeline can differ from case to case.

“While time is still very important, the most important piece is that everyone is still following all those other protocols, so masking, distancing, and all of that,” Muurisepp said. “The focus is on the positive case. Those contacts certainly are a close second to that. But within the six-to-eight hour period of time is the ideal”

Broderick, who remained asymptomatic through her isolation, said the Massachusetts COVID Team was the first to conduct her contract tracing and inform her she should be released 10 days after her positive test.

“I got a lot more information about my current status from the MA COVID Team than I did Emerson itself,” Broderick said. “[It was] stressful because I wanted to know that I had people in my corner to help me through this, and it didn’t really feel like I did.”

Megan Dodge, the college’s COVID Healthcare Coordinator, said Emerson communicates with Massachusetts’ Contact Tracing Collaborative and the Boston Public Health Commission daily.

“They do their own outreach, their own contact tracing and report up throughout state organizations from there,” Dodge said.

The state completes outreach independently from the college, which some students said led to confusion when information didn’t align. Dodge said the state used to contact students on the 10th day of quarantine or isolation to notify them they could be released, whereas the college released students on the 11th day of quarantine or isolation.

“The CTC has now committed to calling everybody on day 11 to try to reduce some of that confusion,” Dodge said.

Max Internoscia, a junior VMA major, tested positive for the virus and went into isolation on Jan. 28. The state called him on Feb. 5, 11 days after the onset of his symptoms, to okay his release. He then had to notify the college of the state’s approval himself before he was released.

“I didn’t know I was supposed to tell the college that—I thought the state tells the college that,” he said. “If I didn’t send that letter … to the Center for Health and Wellness, I don’t think I would have gotten out that day.”

Junior Max Internoscia

Dillan Lincoln, who tested positive while he was in quarantine for being a close contact, said the MA Covid Team called often to ask about his symptoms during his 12-day stay in Paramount—a stark contrast from the college’s dearth of outreach.

“It was better communication than the damn school,” he said. “They actually called and checked up on us.”

One of the primary frustrations, students said, was not knowing who to turn to when a question or issue arose, as their cases were managed by several separate college departments. In order to get an urgent question answered, students had to call the Emerson College Police Department to be connected to the Residence Director on duty. Most on-campus residence halls have a designated RD, rather than the rotating “on duty” system in Paramount.

Internoscia said communication was fractured, as he continually was “tossed around from department to department.” When Broderick needed an urgent question answered, she called the personal phone number of Resident Director Ashley Gravina, who she said then got “mad” at her for calling.

“They could have been a little bit more compassionate towards our situation,” Broderick said.

Release dates—a beacon of hope for many students as they tick off their days of solitude—were a common area of confusion. Internoscia said his release date was changed multiple times by the Center for Health and Wellness before he was told that matter was under the purview of the contact tracers, who fall under a different department.

“I was not told when I was going to leave until halfway through, and I had to hound people for calls—and the thing with me is that I didn’t know who to call,” he said. “I was pretty much an emotional wreck, being in there for the first five days, not knowing when the fuck I was going to leave.”

Lincoln also experienced limbo with his release date. After a miscommunication regarding the date of his symptom onset, his release was erroneously pushed back by five days.

“I was like, ‘There’s something wrong here,’” Lincoln said. “I had to jump through so many hurdles. It was just so many curveballs thrown at us communication-wise.”

Emerson, Tufts Medical Center, and the state’s Contact Tracing Collaborative coordinate to determine a date based on onset of symptoms or date of exposure, Muurisepp said.

Emerson’s testing site at Tufts Medical Center.

Some students encountered broken or unsafe environments in Paramount itself, navigating potentially dangerous spaces as they handled their symptoms and a high-stress situation. Nearing the end of Internoscia’s isolation period, his toilet broke. Not wanting to switch rooms so close to his release, he reported the issue to Anglade.

Days after Internoscia checked out, Broderick had to leave the same room after three days when the toilet broke again. The college moved her to the adjacent room, where she noticed what appeared to be black mold on the ceiling of the shower. A day and a half later, she switched rooms again.

What appears to be black mold in one of the showers in the Paramount residence hall, currently being used for quarantine and isolation housing.

“I moved to the third and final room, and I felt like I could breathe easier,” Broderick said. “If I had actually had respiratory problems, and like I was actually really sick with COVID, that would have just been horrible.”

Anglade says facilities members periodically walk through each space to ensure everything is functional.

“Just like sometimes in your residence hall, every now and then, something doesn’t work,” she said.

Due to the non-centralized process of managing quarantined students at the college, students said essential services continually fell through the cracks. While in isolation, many of Broderick’s questions and concerns went unaddressed.

“All of our trash stunk up all of our rooms,” she said. “They told us they would email us when we could put our trash outside but then they never did. I took the lead and I put my first bag of trash outside because I was like, ‘I can’t handle this anymore.’”

First-year Katie Broderick.

Calvillo said laundry was also difficult to coordinate. The college—through an unsigned email from [email protected]—alerted her on Tuesday Feb. 16 that she could do her laundry on Monday Feb. 1. They later clarified the error.

Moving into Paramount on a weekend, Lincoln said, posed a unique set of problems—and proved even less conducive for communication.

“It was just really bad timing because we moved in on a Friday, and Saturday and Sunday came, and I had a few questions and a few of my roommates were struggling and they had a lot of questions as well, and they were just not very great at getting back to us,” Lincoln said. “There’s not a second line command. Whenever they’re not there, they’re not there.”

Internoscia echoed Lincoln’s sentiment, saying the weekends were a void for communication.

“You have students in quarantine who cannot leave and they’re there in the dark for two whole days on the weekend,” he said. “There really should be a daily call into all these kids that are in quarantine just to ease their minds a bit and get the most up-to-date information.”

Dodge said as of last week, students in quarantine and isolation housing started receiving one or more daily calls from college contact tracers. Prior to this, Muurisepp said there was regular outreach from contact tracers, state contact tracers, and OHRE staff “as needed.”

Anglade noted members of OHRE now also conduct bi-weekly intake Zoom sessions for students entering quarantine or isolation housing to answer questions, but Calvillo said it didn’t yield long-term peace of mind.

“The gist of that first Zoom call very much felt like, ‘Don’t ask, we have it [under] control’… And then it was just completely left up to us,” Calvillo said. “That was the most frustrating part of it—we had to be the ones to take charge of everything.”

The process of releasing some students also proved riddled with inconsistencies. Calvillo was released on Feb. 19, which she believes was triggered by receiving another negative test result. Reyes, however, was not released until the next day, even though they all had the same exposure date.

“Once I got my negative and they told me that I can leave, then that raises the question of like, ‘Wait, if you’re leaving then what about the rest of us?’” Calvillo said. “I was kind of scared to ask any questions at that point.”

In the introductory Zoom meeting, college officials told students who were close contacts they would need to be retested in order to be released.

“We never really heard from them, so we had to reach out to someone and be like, ‘Hey, when can I go get retested so I can leave?’ And then they’d be like ‘Oh, today,’” McCormick said. “It’s like, if I had never emailed, would you have ever told me?”

When McCormick was released on Feb. 19, she filled out her symptom tracker, where the first question asks if you’ve been exposed to anybody with COVID-19 over the past 14 days. When she answered yes, she was locked out of Little Building. Anglade told her she should have answered no to that question, as that exposure was already on file.

“The only thing you want to do is leave, so when it’s obstacle after obstacle, I was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” McCormick said.

The quality of the twice-a-day food deliveries to students in Paramount has been called into question as well. Some students complained of minimal hot meals or soggy food, but in other cases, the menus turned potentially life-threatening.

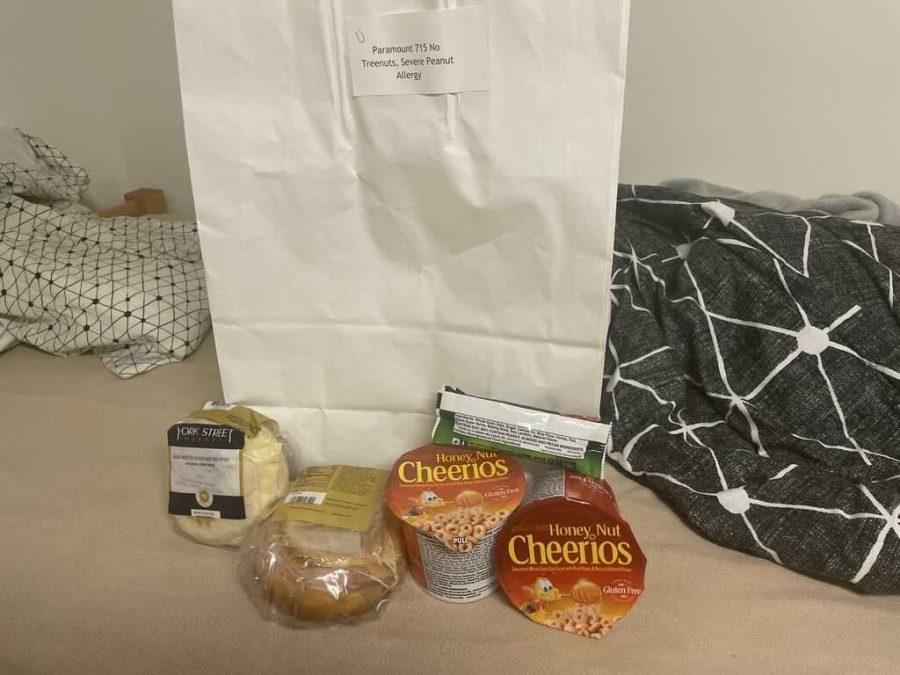

Senior Sean Facey, who has a severe tree nut and peanut allergy, received a breakfast and lunch food pack labeled “nut free” when he was in quarantine earlier this month. The pack contained a breakfast sandwich, lunch sandwich, a salad, Honey Nut Cheerios, and an orange.

The sports communication major could eat only the orange—everything else was pre-packaged by York Street Market, which makes its food in the same facility as nuts. He received a replacement pack by 11 a.m., but was unnerved by the oversight.

“How did it get to this point where I had to basically take my dining experience in quarantine into my own hands and reach out to them on my own rather than them actually just taking care of it?” he said.

Anglade said Dining Services has begun doing Zoom calls with any student in on-campus quarantine or isolation to determine specific needs.

Overall, Internoscia said it felt like many of the details of his quarantine were up to him to manage, often requiring him to repeatedly press the appropriate channels.

“The burden of dealing with my own case was on me completely,” he said. “I didn’t feel like there was anyone in charge of me. I felt like I was in there on my own recognizance.”

While he said the individuals who helped him were kind and helpful, systemically, the college left much to be desired.

“Everyone’s waiting on someone else for an answer,” he said. “It’s multiple departments in one discussion about COVID, and I don’t think they talk to each other.”

Lincoln said the consequences of his diagnosis were worse than the diagnosis itself.

“Dear Emerson students: You don’t want to get COVID or be a close contact, because you don’t want to be in Paramount,” Lincoln said. “Having the virus sucks, but Paramount—you do not want to be in there.”