Almost five years after the “Black Lives Matter” mural was painted at 16th and H Street in Washington, D.C., the letters have been peeled from the ground as the road begins to be repaved.

Construction crews began working at the site on March 10 following threats from Republican congress members and President Donald Trump’s administration to withhold $1 billion in funding from the entire District’s fiscal year budget.

In June 2020, Mayor Muriel Bowser ordered the construction of Black Lives Matter Plaza, where two blocks were painted with yellow lettering to memorialize the nationwide protests that followed in the weeks after Minneapolis police officers murdered George Floyd, a Black man who was suffocated to death in 2020 after an officer kneeled on his neck for nearly 10 minutes.

Now, some protesters say the demolition of the plaza has called them back to the street.

Margie, who asked to be identified by her first name only out of fear of repercussion, stood at the end of the construction site for hours holding a “Black Lives Matter” sign.

“I was very proud of the mayor at the time for putting [the mural] in,” Margie said. She acknowledged that Trump put Bowser in a difficult position, but is disturbed by how the president is using D.C. to bargain. “I think it’s a travesty to try to pull up the symbol of something that was so important,” she added.

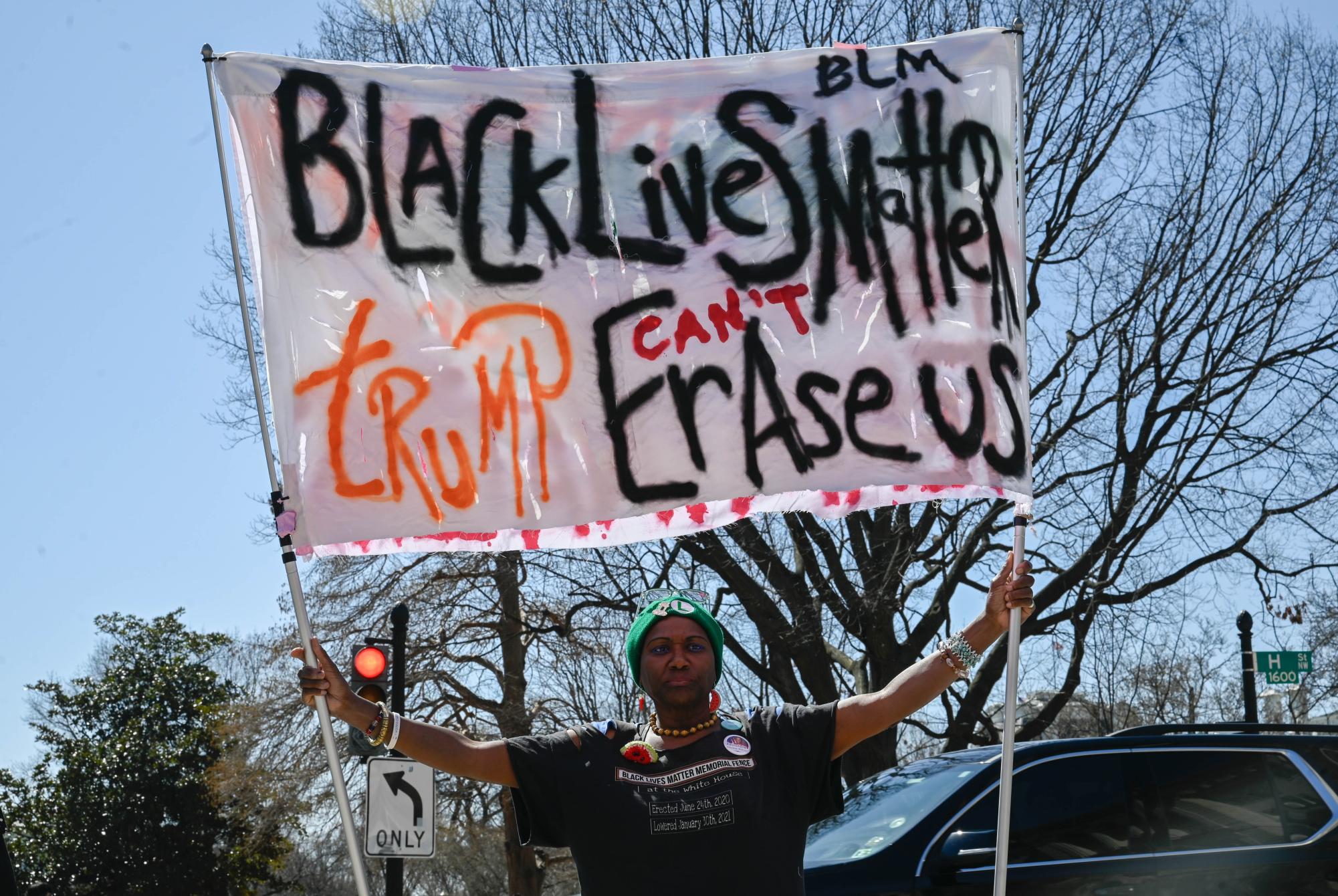

Margie was joined by Nadine Seiler, who considers Black Lives Matter plaza her “home away from home.” Seiler lived on the painted street for three weeks during the Black Lives Matter Memorial Fence vigil—a months-long tribute honoring Black police brutality victims—and she felt the need to come back.

“I came here to witness it,” Seiler said, while hoisting a double-sided cloth sign reading “Black Lives Matter,” “Trump Can’t Erase Us,” and “Thanks Trump: Taxes Tariffs and Terminations.”

“There’s a sense of disappointment, there’s a sense of anger, there’s a sense of frustration,” she continued. But, to Trump, she emphasized: “You will not erase the contributions of Black people, you will not erase the contributions of minorities, you will not erase the contributions of women.”

Several other onlookers stopped by the construction site to watch the crew’s second day of breaking ground, getting as close as possible to the roaring jackhammer. People took photos, videos, and even pieces of the mural home with them.

Just before clearing the rubble with excavators, one construction worker sifted through the debris, looking for pieces marked with the yellow paint that were once part of the “Black Lives Matter” text. With a smile, he handed the chunks of paint and concrete to a small group of onlookers, who held out their hands and waved him over. Recipients remarked that they’d preserve or make art with their pieces.

Even as the mural fully disappears in the coming weeks, Margie echoed Seiler’s sentiments—“You can’t erase Black history.”