Five students in quarantine and isolation housing in the Paramount residence hall, cut off from many of the college’s services and completely dependent on twice-a-day meal delivery to their door to eat, have reported abysmal and sometimes life-threatening menus.

On Feb. 9, when senior Sean Facey woke up for his fifth day of quarantine in Paramount, he was greeted with a food pack labeled “nut-free.” The pack contained a breakfast sandwich, lunch sandwich, a salad, Honey Nut Cheerios, and an orange. The sports communication major, who has a severe peanut and tree nut allergy, could eat only the orange—everything else was pre-packaged by York Street Market, which makes its food in the same facility as nuts.

Though he immediately called Food Services and a replacement food pack was delivered around 11 a.m., the experience was troubling, he said.

“I’m not a very picky guy for the most part—I’ll eat whatever is given to me as long as it doesn’t kill me,” Facey said in a Zoom interview from quarantine. “It’s just kind of stunning to me that a lot of this stuff keeps slipping through the cracks and that there was actually a time where I was able to just theoretically not have any food available for me to eat.”

Facey went into quarantine on Monday, Feb. 5, after his friend junior Jeremy Guerin tested positive. Facey, Guerin, and Guerin’s three suitemates, senior Anton Lee (who later also tested positive), and juniors Justin Voegelin and Jeff Pratt, packed up their belongings in their Colonial Residence Hall suites to go to Paramount for isolation and quarantine.

Isolation is for those who are “known or reasonably known to be infected” with COVID-19. Quarantine is for those who may have been exposed to the virus, but are not showing symptoms.

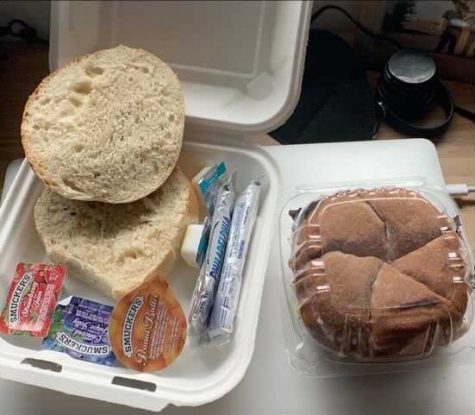

Each of the students described the substandard food delivered to them twice daily; a breakfast and lunch pack in the morning, and a dinner in the early evening. Christie Anglade, director of the office of housing and residential education, said students also receive a “snack pack” delivered twice a week. Students in Paramount have a mini fridge and microwave.

Lee, who was also placed in quarantine on Jan. 24 and released Feb. 2 before returning just three days later, said he then once received an “old sandwich” for lunch, eating only the meat he peeled off the bread.

“The mayonnaise had liquefied,” Lee said. “It was kind of almost watery at the bottom—it all kind of pooled at the bottom.”

He then contacted dining services, who later responded by delivering him a hot breakfast of eggs, hash browns, and turkey bacon. Lee said the college, though responsive when concerns are raised, has neglected to consistently provide them with better food without prompting. During this quarantine, he described wet, unlabeled wraps for lunch.

“I was like, ‘Hold on. So you had hot breakfast food that you could have given me but you chose not to do it just for whatever reason, because you probably knew I wasn’t going to complain about it, I was just going to suck it up and eat it?’” he said. “It should be the standard.”

Guerin, who struggled with symptoms of the virus including a fever, a headache, and losing his sense of smell and taste, said the lack of adequate nourishment took a toll on his body.

“When you’re sick, you don’t have that much appetite to begin with, but when the selection of food is what it is right now, that’s when it really becomes a problem for me, because I didn’t have a ton of energy,” Guerin said. “I was in basically a stupor, and little to no food is not helping that.”

Lee said he and his friends have requested double portions, because they eat so little of the food which often arrives damp from steam accumulated along its journey from the Dining Hall to Paramount.

“Every single time your lunch or dinner comes, it’s soaking wet,” Lee said. “Everything inside is a weird mix of too steamed and not cooked.”

Voegelin said the bags of food contain fruit and bottles of water piled atop the box with the main meal.

“By the time I get to my box, it’s scrunched down, it’s just completely crushed,” he said. “I’m just constantly hungry, because I can’t eat this food. It just doesn’t like suffice and it’s just twice a day is not enough.”

During his most recent bout of quarantine, Lee said he emailed Anglade after a day of receiving no hot food—which he said has happened a couple of times. Anglade responded on Feb. 9 that caring for the number of students in Paramount—seven in isolation and 31 in quarantine, as of Wednesday evening—was putting a strain on their food delivery capacity.

“Some of the meals have to be prepackaged at this point because of the number of people that are in quarantine and isolation—prepping over 40 meals for delivery in a limited period of time that need to be delivered across multiple buildings presents various challenges,” Anglade wrote. “As the number of students in quarantine and isolation grow, that means that it’s not always possible for every meal to be a hot-prepared meal.”

Lee said he did not understand how the college’s quarantine and isolation program could be choked by only 40 residents.

“You can’t have a system that’s like, ‘Well, we could use all of Paramount, but if 10 percent of Paramount gets filled, we’re fucked,” Lee said. “What happens if there’s 60 people in here? What happens if there’s 80 people, 100 people, 200 people?”

Anglade told The Beacon OHRE routinely coordinates with Dining Services to ensure students have adequate food when they enter Paramount and can report any issues that arise—including if students have particular dietary restrictions.

“I met with dining earlier today and they had actually said, ‘You know what, what we’re going to start doing is anytime a student goes into quarantine or isolation, if they have any dietary restrictions, we’re going to go ahead and do a phone call with them to work out what they actually mean so we can go ahead and meet those needs,’” she said. “So if a student will share it with us, we’ve been pretty quick to go ahead and respond to that.”

Facey said Anglade’s sentiment failed to align with his experiences.

“Early on in the quarantine process everyone was incredibly helpful and communicative,” he said. “Over the first 24 hours, any questions I asked got immediate answers. Since then, though, it’s been spotty at best. Sometimes they’ll respond to emails within minutes, sometimes it takes days. It’s just crazy that a college renowned for its communications school can be so woefully inept at communicating with its students.”

Beyond the insufficient meals, Guerin described a general lack of communication from the college regarding his isolation. By contrast, Guerin said he received frequent communication from the state’s Contract Tracing Collaboration, who told him that he would have to show no fever in order to be released ten days after testing positive without the aid of any medication, a detail he said the college did not inform him of.

“It’s just kind of disappointing,” he said. “I wish that they had been a little bit more forthcoming when it came to information that may have been actually pretty helpful for us…they basically just left me in here for the next ten days to, like, culture, like a petri dish…it’s kind of like a punishment.”

Guerin told one of the contact tracer representatives about the food conditions. Guerin was later informed that they’d told the college that students were complaining.

Lee said it often feels like he and his friends check in on each other’s health more than the college does.

“Emerson—they do a good job of keeping people safe in terms of protocol and the system,” he said. “But when it comes down to how they act and treat everyone in here, it’s like we’re afterthoughts. It’s like we don’t exist.”

Pratt echoed Lee, saying Emerson’s preparation in terms of protective measures, like testing and contact tracing, far outnumber the infrastructure they have set up for students who test positive.

“It’s almost like they put so much effort into their protocols to keep us safe, that when people actually get sick, they’re not prepared,” Pratt said.

In the last four months, Facey has filled out the college’s dietary restriction form three times, and believes the administration has his allergy on file. He was diagnosed with his allergy at three years old, so he said he’s used to being vigilant about what he eats. He said he’s worried, though, about other students, who might not take their allergies as seriously.

“I just don’t understand how it got to that point where I had to basically take my dining experience in quarantine into my own hands and reach out to them on my own rather than them actually just taking care of it,” Facey said.

Ann E. Matica contributed reporting.